First-Hand Accounts of the 151e R.I.

Sub-Lieutenant Roger Campana

Charles Louis Roger Campana (class of 1913) was a 21-year-old graduate of the elite military school, Saint-Cyr. Made a second lieutenant he served with the "15-1" in the hellish battles of Argonne forest, the slaughter of the Second Champagne Offensive and nightmare of Verdun. I will be placing his account up in segments, as I begin the slow process of translating and transcribing his memoirs.

Abstract of Campana's baptism of fire in the Argonne

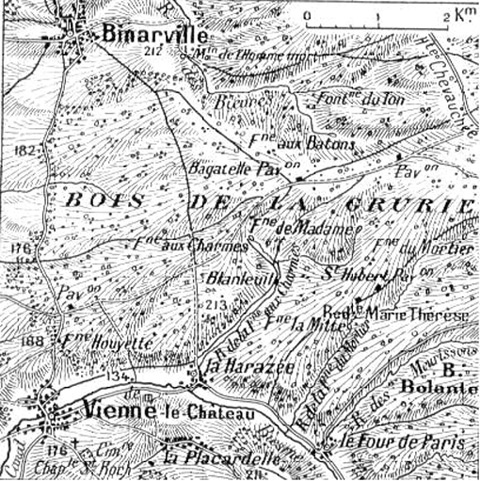

The following account comes from Sub-Lieutenant Roger Campana. Fresh from his graduation from the elite Saint-Cyr military academy, the 21-year-old Campana would soon receive his baptism of fire in the trenches as the war turned a new year. He was eager to finally get into the fight. At the start of 1915, the 42nd DI (of which the 151st RI was apart) was assigned to the chaotic labyrinth of the Argonne, in the Bois de la Gruerie sector (sinisterly given the nickname Bois de la Tuerie – "Slaughter Wood"), just north of Vienne-le-Château and la Harazée. Tightly packed pines, thick vegetation and innumerable steep ravines greatly reduce visibility and enhance the sense of claustrophobia. Mine warfare was a defining characteristic of fighting in the Argonne, as well as sudden, deadly raids and ambushes. It was a very different experience for the regiment which had previously come from the flood plains of Belgium. The snow, mud and cold also contributed to the daily hardships of life in the Argonne. The 151 was put in front line positions in the subsectors of Fontaine-Madame and Blanloeil [Blanleuil]. From the first days that the regiment arrives, it is submitted to localized enemy raids.

Campana, new to the regiment, was assigned to the 5th Company, under the command of Sous-Lieutenant de Sainte-Croix. Arriving at La Neuville-au-Pont on 17 January 1915 with a group of replacement troops, Campana heard for the first time shots fired in anger, a low rumbling almost like a far-off storm. Gradually, it increased in volume and the sound changed to a serious rolling noise that reminded Campana of heavy carts bouncing around paved streets. The detonations seemed to reverberate a hundred times over and again. Then the rolling sound became louder, more resonate, more harrowing. Suddenly a whole picture came into view. Against the gray sky little white puffs that looked for all the world like snowflakes: shrapnel shell bursts.

--“What do you say about the music?” Sous-Lieutenant de Sainte-Croix asks as he approaches Campana.

--“Not bad, but it sounds better at the [Paris] Opera,” Campana retorts.

--“You see, it’s not so terrible.”

--“What a joke! I know that shrapnel bursting 10 km away can’t cause a scratch! All the same, I've wanted to hear it for a long time, this music, and I'm very.”

Passing through the village of Vienne-le-Château, now in ruins, night began to fall. All around, the ground was pocked with shell-holes. Walls cut down by gunfire, turned-over caissons, splintered trees, lined the road like phantoms, as the overflowing little river reflected sinisterly the pale dusk light. The cannonade grew in intensity. The individual detonations of the shells could now be clearly distinguished, followed by the quick stab of light that illuminated the sky. A heavy downpour began, lending it an even more dismal mood. Entering the first trenches 2 km in front of the village, the fusillade continued and Campana thought he heard the fizzling sound made when green leaves were thrown into a fire. Occasional illumination flares lit up the dark shadows around him, casting a bloody iridescence across the trembling heights and the serrated saplings. Campana told his men to observe the greatest silence as they continued to make their way through the trenches, drawing closer to the enemy lines.

The floor of the trench consisted of a thick, sticky mud that made progress laborious. Stray bullets whistled overhead the quite column of men or burrowed into the trees around them with a sharp crack. Occasionally a fuse shell burst in the woods, the sound of its explosion reverberating between the steep ravines like a big thunderclap. They passed by stretcher-bearers heading back down carrying dead bodies on their stretchers, turning Campana’s blood a little cold. Halting at an embankment, they stood around for two hours awaiting orders under the chilly rain. Finally the liaison agent of the 5th Company arrived to lead Campana and the replacements to their trenches. They move forward for again, at each step stumbling against felled tree trunks and shell-holes full of icy water. After a quarter hour, the guide announces to the lieutenant that they have arrived. The night is so dark that he has no idea of where he is. But he could just make out from the surrounding darkness a large black hole like the entrance of a cave. It was a covered trench and a voice called out from it:

--“Mon Lieutenant! I’m in charge of the platoon of the 147th that you’re relieving. Here are the co-signs.”

--“What’s your rank?”

--“Corporal.

--“Have you been attacked?”

--“Sometimes, mon Lieutenant. Fortunately we have a machine-gun and that mows ‘em down.”

--“Has the enemy’s artillery picked up?”

--“A bit. Today we received some fuse shells and a percussion shell this morning that caused a collapse in the trench.”

--“Have you cleared it out?”

--“Not completely, but it’s passable.”

--“Good, I thank you.”…

“Au revoir, mon Lieutenant, bonne chance,” and with that, the relief was completed without further incident.

Posting half his section on watch and the other half on rest, Campana made a futile attempt to ascertain the layout of his positions before letting himself collapse from exhaustion among his men in the mud under the falling rain.”

When Campana awoke the next day, 18 January, he set off to inspect his men and his position. The temperatures had fallen and the rain had by that time turned to snow. A fusillade of shells were bursting all around, though Campana was elated – this was his long-awaited initiation to combat. Suddenly Campana realized he had been wounded but only just a light flesh wound on his right thigh. His first day in the trenches and he had already been hit, even if it was only a fine blessure. Campana went to lie down on litter made of sapling branches set up by his men. Dozing off, he was suddenly awoken by a violent detonation of a German 77 shell that exploded close by. So exhausted was the lieutenant that he almost immediately fell back to sleep, only to be rudely woken again by a second explosion even closer. Then, a third shell blast and a fourth even closer still. Raising himself up Campana heard the voice of one of his men:

--“Mon lieutenant,” cried out Niquet, a little sergeant from the class of ’14, “I really think that we are rep--“

‘I didn’t hear the end of his sentence. Suddenly I felt as though I had been punched square in my face and I fell back. I laid there for several moments completely dazed. When I came to, my nose, my mouth, my eyes were filled with dirt and my ears rang with an uninterrupted rumbling, as if a locomotive had come off the rails. But all of this suddenly dissipated before the horrible sight in front of me. I froze, terrified. Niquet lay at my feet, his head crushed, formless. His greatcoat was covered with mud and brains. Blood was splashed on it in places.’

Campana had been wounded again. Looking down he saw that his breeches had been torn in two spots and a shell fragment had penetrated into his right thigh, though not too deeply, and blood began to seep from the wound. Quickly cleaning and bandaging the wound, Campana was soon back in action. Later in the morning, the lieutenant “had the pleasure” of firing on a small party of Germans who had exposed themselves on the crest of a ravine 600 meters off. Firing a burst, the party quick dispersed like a flock of sparrows. He could not be sure if he had killed or wounded any at that distance though. He was more sure that his act had brought on a salvo of enemy shells later in the afternoon. “If our trench is targeted, we’re going to dance tonight.”

Later on, Sous-Lieutenant de Sainte-Croix took Campana on a tour of the lines. The German first line trench was only 50 meters away and to show one’s head over the top of the parapet was sure death – there were bons tireurs about. Lying between the lines, stretched out on the slopes, Campana could make out the gray-clad bodies of the German dead and the dark blue-clad bodies of the French. They had fallen in the previous attacks in this area, left to rot between the lines. Unnerved by the continuous bombardment, men frequently fire at the enemy lines though they can see nothing. Adding to the cacophony of noise were the stray bullets that zipped high overhead, sounding like the buzzing of bees. They struck with a dull thud when they buried into the ground and meowed loudly when they bounced off a hard object, ricocheting off in a different direction. Campana also claimed to observe exploding bullets smash into the trees, a claim often asserted by French soldiers suspicious of the conduct of the German invaders. More likely, they simply perceived the bullets to be exploding when in reality this was the destructive effects of normal bullets against a tree. Still, no attack came, and the men simply waited in the cold, shivering in their muddy holes. Disillusioned and a little naively, Campana wonders to himself: ‘Where are the beautiful charges of former times, sounded by bugles, beaten by drums, under a blue sky in the light of day? Will these times return? Why not?’

The next day, 19 January, Campana begins to wonder if his hands hand been dirty when he had bandaged his wound and if his wound had gotten some mud in it, for he was now suffering terribly from it. Changing his bandage he noted that his thigh was swollen up and a large red and purple patch surrounded the wound. Every time he came down on his right leg, he experienced sharp shooting pains. But Campana refused to go to the ambulance for fear of being sent back to the rear areas. Being evacuated after only three days in the trenches was more than he could bear. The lieutenant spent the rest of his day briefing de Sainte-Croix about the bombardment the day before, and talking to his men about their families, their lives before the war and their hopes for the future. He had nothing but respect for these men who calmly and bravely sat in the mire, under the bursting shells. His chats ‘chasse le cafard’ (“chased away the blues”). Campana listened as French 75s whistled loudly overhead, exploding in the German trenches with a frightful, sinister noise.

‘For several minutes it was frightful. You could say that it was raining 75s, the explosions merged together: bziou!...bziou! trac!...bziou!...bziou!...trac!...trac! trac! trac!...trac! … What music!’

Suddenly the barrage ceased and silence returned to the lines as night fell. The weather grew colder, and the men huddled piteously together in their trench, the sticky mud rising up to their knees in some places and up to their thighs in others.

‘It is a sort of greenish-brown clay, really awful. The more you want to walk, the more you sank in and if you remain in place, it’s even more atrocious. It feels like your feet are being gnawed at by a thousand ants or, in some moments, like they are covered in burning coals. They swell up from dropsy, they turn red, purple, brown, as if they were becoming gangrenous. Tonight three of my men have had their feet completely frozen, they were evacuated this morning. It’s the leg-wraps that are impairing the blood circulation and it’s impossible to take off one’s shoes, for if an attack goes off at this time it would have to be made bare-footed in the snow. We don’t think about death. The whistling bullets, the bursting shells, they don’t frighten us. We don’t pay attention to them. But this cold, this terrible cold! My feet felt like blocks of ice. Oh, I only wished to attack, that would at least warm us up a bit.

'I have a violent migraine and my eyes burn as though I have a fever. Is it my wound or the temperature that causes that? During the night, an icy wind began to blow and we couldn't get out of our holes to warm up. We had to remain crouched in the mud, tortured by the cold that bit into the whole body atrociously. The next morning, ten men from my section were evacuated out of the forty I had received on the 17th, and I was suffering more and more. The fever was becoming very bad and I again felt in my intestine pain which, though dull at first, soon became intense, intolerable. I felt nauseous and dizzy. I had to lie down on my litter of pine branches and no longer had the strength to lift myself up. My throat and lungs were burning, and I felt as though I was breathing sulfur. Suddenly there was no pain. I was fading fast and I thought it was the end. A sweet torpor overcame me, and then I passed out.

'When I woke up I was in a room in the chateau of La Harazée transformed into an ambulance. That's where de Sainte-Croix had ordered that I be transported. There weren't any beds nor any straw. I had been laid out on a stretcher on the ground. I was alone in my room. It was very cold. From the neighboring areas I could hear the cries of a number of wounded. Outside it was snowing heavily, a fusillade crackled away, shells burst in the village, roof titles crashed down with the sound of dishes being broken.

The Major-[Medecin] [the Chief Medical Officer] Idrac came to see me in the evening:

“Eh ‘bieng’ [ah bien, “alright”] my dear boy, it would seem that you’re not used to this cold ’heing’? I’m going to evacuate you ’deming’ [demain, “tomorrow”] evening. I'd make you leave tonight, but there are some ’grin’ [grands, “seriously”] wounded who can’t ’attindre’ [attendre, “wait”]. Right now I’m going to give you a little benzo-naphthol. See you tomorrow!”

I had a dreadful night. It felt like I was being stabbed with a knife in the chest every moment. The next morning a nurse came to give me a wadding wrap, but the pains didn’t diminish. He remained with me a long time and told me that before the war he was a literature teacher at the Verdun middle school.

Around 2:00 PM they brought a gravely wounded officer into my room. It was a terrible surprise to see that I recognized my poor comrade, Denevault [Sous-Lieut. André Denevault of the 94e RI]. His greatcoat had been removed. His shirt seemed to be made of red muslin it was so inundated with blood; his face looked like wax; his eyes were half-closed with dark circles; but he had not lost consciousness. He saw me, a feeble smile spread over his pale purplish lips. He signaled to the nurses to place his stretcher next to mine. Slowly he reached out to hold my hand. I gave him mine, which he shook convulsively. Major Idrac came to examine the wounded man. He nodded his head:

“Go look for the chaplain,” he said.

That meant there was nothing he could do, he was a goner. The priest sat down to give him his last rites. Soon my comrade’s grip became very fidgety. He made two or three efforts to lift himself up. An expression of anguished suffering came over his face:

“Mam...Mama!”

Then he no longer moved. He had ceased living, his hand still holding mine as last goodbye. One of my nurses told me the unfortunate man had been hit in the middle of his chest by a shell fragment while he was writing a letter to his mother, as evidenced from the letter he still held in his hand when they had recovered him. [It read:]

“Dear Mama, it’s really cold but we sense the enemy is very close by and that keeps us warm. We are waiting impatiently for the moment to pounc…”, and under this unfinished word the pencil had traced a large black line. Death had passed by. His mother, poor lady! And in is agony he thought always of her. Perhaps my hand that he still pressed, which I ever so gently disengaged had given him the illusion of pressing her dear hand. His mother! His last thought, his last cry had been for her: “Mam…Mama!” Oh! What a dreadful afternoon I passed there and it wasn’t over yet!

In the evening, the motorcars came to look for us. In mine there were two chasseurs, one laid out to my right, the other above me. Major Idrac came to see me before I departed:

“Eh ‘bieng’, what do you think of your sleeping-car?” This dark pleasantry was far from making me laugh. The motorcars took us to Sainte-Ménehould. The moved along the pot-holed road very quickly and the uninterrupted shocks made the two wounded men groan. With each strong jolt the one to my right would cry out:

“I’m going to die! I’m dying! I’m dying!” And the other in a more feeble voice would always repeat the same phrase: “I'm losing all my blood…I'm losing all my blood!”

When we arrived at Sainte-Ménehould, my neighbor to my right complained. The other was dead. In the moment I asked if I had not been the victim of a dreadful nightmare. This white road, the detonations, this bland smell of blood that mixed with the acrid vapors of the benzol, these painful shocks, the agony of these two men laid out next to me in the night and for whom I could do nothing, their cries of suffering, their cries of anguish – what awful memories!

The worst thing in war isn’t the fighting, the bursting shells, the whistling bullets, the vibrant ringing out all around, this noise, this continuous grating and excited thundering. You don’t think about death. But when you had to remain amongst the wounded, amongst the anguished, amongst the bodies of the dead. Oh! Such an atrocious thing! There, where there was no more racket, no more intoxication, but only the dark silence in between the cries, moans, groaning. The body no longer fights, the spirit is no longer overexcited. You see reality in all its horror. You feel sorry for these poor men who just yesterday full of strength and life will be tonight bloody rags in a tent-canvas and covered with two meters of earth. You shudder to think that tomorrow you will have to perhaps go back through the same trials and become worm food like them. We’re afraid!

The next day Campana was taken by train to Nice to recover. He had lasted only four days in the trenches. He would return to the regimental depot at Quimper in April and requested he be sent back to the front. On 29 April 1915, he arrived back at La Harazée, walking back into the first-aid post he had been evacuated from in that cold dark month of January. Campana would be reassigned to the 4th Company under Lieut. Vincent (who the men called Gros Noir -- "Big Black", the same nickname for large caliber artillery shells in reference to the color smoke they produced upon exploding) and given command of 1st Section. Curious to see who among his old veterans were still in his former company, the 5th, Campana was disappointed to learn that none remained. He was told that the regiment had been decimated twice since he had been evacuated, on February 15 and March 1.*

[Note: more likely the date was February 17 when -- on top of weeks of steady losses -- the regiment suffered 158 casualties, including 15 killed, 99 wounded, and 44 missing. Among the dead was battalion leader Commandant Segonne. On 1 March the regiment lost over 300 more (along with a number of junior officers), including 37 killed, 220 wounded, and 46 missing.

Abstract of the Second Champagne Offensive:

After surviving fierce fighting in the Argonne forest, Campana is evacuated from the front again on May 19, 1915 when he was struck by a large stone projected from the explosion of a mine. The force of the impact caused him to suffer an appendicitis attack requiring immediate operation. Following his operation in June and a subsequent period of recovery and then training, Campana chooses to ignore the Medical Commission’s decision that he not yet return to front line service and puts in a request with the major of the 1st Battalion (151 R.I.) to overrule it. The major consents and Campana rejoins the regiment on October 3, along with another officer comrade from St. Cyr, Arthaud de La Ferrière. Campana is assigned to 1st Company. The 151 had just arrived at Mourmelon-le-Grand for a brief rest after spending a week under fire and would depart again for the front the next day. Before going back up to the front Campana admits that he "more and more has become a fatalist and like the Muslims, I believe that our Destiny is written in advance and that one cannot change the place of exit of our parable of life."

From Mourmelon-le-Grand the regiment moves up to the line on the night of October 5-6 in preparation for an attack to be launched the following day (Oct. 6). The "15-1" returns to the Aubérive-sur-Suippes sector, where it had fought during its first engagement in the offensive from September 25-30. The men fully anticipate that it will be a “hot” affair, as the German positions they are charged with taking are defended by a veritable sea of barbed wire. They fear a repeat of the tragic fate which befell the regiment on September 25, the opening day of the offensive. On that day, after advancing only 100 meters, most of the regiment was stopped in its tracks when it suddenly encountered a completely intact belt of German wire entanglements 50 meters deep. Concealed by a hollow, it had been left untouched by the preparatory bombardment. The regimental historical noted somberly that entire companies were wiped out in place by machine-gun fire as the men desperately struggled in vain to cut through. Whole lines of men lay in front of the wire or strung up macabrely, hanging from the the entanglements. Only minimal gains were made. Since that date, the French offensive on a whole had ground to a halt.

The specific subsector they were assigned to was east of Aubérive opposite the German position designated Salient E. In the night of October 5-6, the regiment is sent to work transforming the first line trench into a departure trench for the coming attack, constructing numerous departure step ways to expedite the exiting of troops. Their objective for the next day is to take the fortin ‘414’ (“small fort” 414).

On the morning of October 6, French artillery opens up a rolling fire on the German trenches, but the men sense that the fire is not having the desired effect. They look out with unease on the enemy wire entanglements that still remain intact. The French artillery fire becomes more violent as the time for the attack nears; zero-hour is set for 1100hrs. At 1050hrs, the heavy 210s begin to smash down on the cupola of the fort. But after each massive explosion, the German machine-guns -- concealed under concrete shelters -- fire a burst for several seconds to taunt their attackers.

“The moment has come: a signal from the Captain, a whistle-blow:‘Forward!’

A bound of 10 meters is made in a disturbing silence, then suddenly a frightful fire of musketry, thousands of bullets whistle by and drill into bodies, shouts of rage, groans, entire lines of blue greatcoats mowed down in place like wooden soldiers and a sudden stop in front of an impenetrable entanglement of barbed wire.

‘Lie down!’

We let the bursts of gunfire pass over head. Our artillery starts up again with a more violent fire and the enemy machine-guns stop firing. I look around me; hundreds of men were lying down in skirmish lines in the plain. The Captain gets up:

‘Stand up and about face!’ he cries. Only about 50 men rise, the others remain laying face down in the grass, they were dead.

I shuddered at the sight of all these dead bodies in light-colored greatcoats who would never make another assault. We went back to our departure trench. The Lieutenant [Garrigues] was among the dead. A half-hour later we renew our attack, but still without success. Our Colonel, the bravest of the brave, Father Victory as the men affectionately called him, came up to ask us to make a third bound. He looked above the parapet and immediately received a bullet in his head; the morale of the soldiers was very affected, but three more times we threw ourselves into the attack again only to break upon the cursed entanglements each time!

In the fifth assault, the Captain was struck down by a shell fragment and I took command of what remained of the Company. Major Brugère reassembled the Battalion in the departure trench. The terrorized survivors didn’t want to leave the trench anymore and began to murmur amongst themselves. Their commander exhorted them in vain:

‘Are you ready to make another go?’

‘It’s a slaughter!’

‘We’re going to get killed for nothing!’

‘For nothing? No, for France! Come on, one last time!’

‘All right, you go first!’

‘First? Yes, certainly!’The Major takes his pipe, packs it deliberately and lights it. He takes ahold of his cane with his hand and dashes forward crying:

‘Forward, my boys! This is for France!’

All the survivors dashed forward behind him; he went a dozen meters and collapsed while the bullets rained down like hail, felling a number of soldiers. And for the sixth time I ordered in my turn what remained of the company back to the departure parallel. An adjudant went up to the body of the Major, leaned down towards him to see if he was dead or simply wounded, but then collapsed on top of his body. A corporal who crawled up to make the same attempt suffered the same fate.

Captain Le Boulanger took command of the Battalion. We were the only officers remaining.

‘Such dishonorable and stupid carnage, I tell you. How do they expect us to take this fort still defended by an entanglement 50 meters deep that hasn’t even the smallest breach and is protected by multiple machine-guns. If we are ordered to attack a seventh time, the men will no longer follow us. It will only serve to get us killed like the Major.’

The order to stop the operation arrives several moments later. Another regiment comes to fill our gaps and the departure parallel is transformed back into a first line trench. But all afternoon the fusillade carried on. The enemy had a disgraceful conduct: he amused himself for several hours turning our wounded and dead into paste. We listened to the German bullets ricochet off the ground, pierce into helmets or drill into the bodies with a dull thud. At 1400hrs, we perceived over the detonations the wailing, the cries of agony, the groans of our wounded. At 1700hrs, only the creeping of Mausers broke the silence. Between our lines, there were only the dead.

We imagine the anguish of our poor soldiers pinned down to the earth suffering as they wait from one moment to the next for the bullet that will give them another wound or finish them off. Certain they could not survive this awful nightmare, they found the strength to stand or crawl back toward us. But they didn't get far: the Germans watching them immediately shot them down. When can we give them the same treatment and massacre them without pity!

Our assault had been a complete failure. Who is to blame? Certainly not our leaders, they've done their duty valiantly. Doubtless it's the artillery that could lay waste such an accumulation of defensive accessories, chevaux de frise, barbed-wire, then crush the strongly protected machine-gun nests. Perhaps if the fire had been more accurate?

The morale of the men at this time is dreadful. First, they were happy to learn that the fight was over. Egoism trumping all, they were just happy to still be alive, that mattered most. Then the knowledge of having escaped death seemed entirely natural to them, so they began to occupy themselves with other thoughts. They criticize the operation, outraged by the results. A few headstrong ones knew how to adroitly sow discouragement, and that was especially easy as the soldiers could see in front of them hundreds of dead bodies -- their comrades just the evening before -- lying between the lines, before the inextricable thicket of metal entanglements. They believed they had been sacrificed for no gain and they were bothered by the notion that the thing could be repeated all over again.

The work of corruption did not happen out in the daylight but I felt it accomplish its devastating work in the shadows. It was going to take both proof of the bad energy and a great amount of will to take it from the hands of these discontents.”

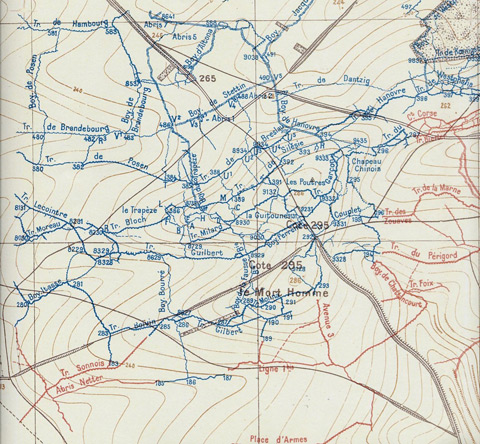

Original map from 151 RI campaign journal showing jump-off positions of the various companies. The blue line represents the German first-line trenches, the brown lines are departure trenches. The 'V's represent the various attack wave zones, with most of the 151 RI assigned to the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th attack waves. The 3rd and 4th companies were assigned to the first wave as flank guards for the 94 RI, 8 BCP and 16 BCP (composing the 1st and 2nd attack waves).

Abstract of Verdun:

Battle of Verdun 1916

On April 6, Campana's company (1st Company) is sent to Point 265 (the lower of the two summits that make up le Mort-Homme) and the northerly slopes of the hill. Fortunately, they had entered at a period relative calm. This would last for two more days, during which time, Campana (a mathematician before the war) continued his studies in a dugout by candle-light. While on patrol the night of April 7-8, the "Lieutenant Mathematician" captured two German deserters. The prisoners warned them of a coming attack. The following morning, was a warm sunny day. Campana was amazed to hear larks singing on the summit of le Mort-Homme. Suddenly, the morning calm was broken as a single shell landed and was immediately followed by a hurricane of others.

By 1100 hrs, the bombardment had intensified to a dramatic level. In a trench to his rear that he had ordered abandoned the night before, eight shells burst almost simultaneously. At noon, the Germans sent the first waves of their assault troops over the top with fixed bayonets.

Some surviving German soldiers attempted at first to play dead, "like rabbits," Campana noted. But sooner or later they lost their nerve and jumped up to make a rush for their own lines, only to be picked off by Campana and his men who noted that the spectacle was a real diversion. The shelling then resumed and this time their machine-gun was hit, blown away by a heavy shell. Once again the German assault waves went over the top.

German soldiers made it into the first-line French trenches below Campana and savage hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Desperately, he fired a red flare to signal the artillery for fire-support and, for once, the 75s replied. Salvoes of shells came screaming down right in the middle of the advancing German waves. Yet still the enemy advanced. When they were only thirty yards away, Campana gave his men the command "baïonette au canon!" ["fix bayonets"]. At that very moment the withering rifle fire of their rifles was coupled by salvoes of short-falling 75 shells. Panic erupted in the enemy ranks and, like rats in a burning barn, "they ran frantically to the right and left."

A counter-attack to take back the lost trenches was immediately ordered, which Campana watched through his binoculars. The counter-attack force was lead by a young lieutenant wearing white gloves who had been a fellow classmate at Staint-Cyr. Soon after, Campana spotted the lieutenant sprawled out dead on the ground, with his conspicuous gloved-hands lying on his chest. Night brought a respite in the fighting, as a large, sinister red moon illuminated the butchery on the slopes of le Mort-Homme. Campana counted over 180 German corpses in front of his section alone. He remained in position on the summit for another week before being relieved. Later, pride filled the "Lieutenant Mathematician" as he gazed at the ragged and greatly reduced ranks of the 151e during the decoration ceremony which followed.

In fact, Campana is one of those soldiers who seemed to somehow prosper in the environment of war. Desensitization, to one's fellow man and to the brutality of war itself, is a common phenomena in all wars. At the end of his third tour at Verdun, he recounted how he morbidly photographed the body of one of his men killed by a shell that hit his own dugout. He even sent a copy of the photo to a friend to prove what a lucky escape he had had. The body had been "laid open from the shoulders to the haunches like a quartered carcass of meat in a butcher's shop window."

Another map of the the Aubérive sector trenches.

Map showing trench lines in the Abérive sector, ca. 1916-17.

After serving a 20-day spell in March 1916 at Fort Douaumont, the regiment was sent over to le Mort-Homme on the Right Bank of the Meuse. His memoirs provide a glimpse into the unique formlessness of the fighting at Verdun.

"They ran forward a few meters, then under the tac-tac of our machine gun, collapsed. . . . not a single German got back to his trench."

"In a few minutes the slopes of Hill 265 were covered with enemy advancing on us. This time we only had our rifles to stop them, and that was not sufficient."