First Hand Accounts of the 151e R.I.

Lance-Corporal Henri Laporte

The regiment is on rest at Pogny when it is ordered to Verdun, roughly 65 km away. A note on dates first. Laporte's record around dates seems to be inaccurate. For example, he notes that the regiment arrived at the town of Verdun on February 25 but the official record and other first-hand accounts state that they arrived on March 9. A best-effort has therefore been made to deduce the correct dates based on the time elapses of in his entries.

III. Verdun (1916)

February 20

[We were put on] alert, and after all were equipped and had received their issue of rations and munitions, we set out marching. While on route, we learned that it had "heated up bad" [ça chauffait dur] over at Verdun. Indeed, on February 21 exactly, a terrible torment raged in the Verdun sector. The German High Command wanted to seize this town and had resolved to finish off the French army. It was the beginning of the great Battle of Verdun.

March 9

After three days and three nights of forced marches through rain and snow, stopping only to eat, we arrive there on February 25. The ground was frozen and slippery, the snow fell continually. The town was bombarded: there were shell bursts, scattered fires. Our last stage had been tough: we've marched without stop for twenty-four hours.

March 10

It was midnight when we reached the gates of the town. After a quarter hour of marching, my company billets in a group of abandoned houses. We were lodged (the men of my half-section and myself) on the third floor, in a room with a ceiling gaping wide open, punctured in the center by a falling shell. A moment later, some poilus from the section brought us some food stuffs (forgotten, certainly intentionally, by the inhabitants).

The snow had stopped falling, but the cold was sharp and the march was made difficult by the slippery ground. For a little while we followed the Meuse, then we obliqued to the right from the first fort of Verdun, Fort Souville* if I remember correctly. After a good hour of marching, we make about a quarter hour halt near Fort Froide-Terre. This fortification was completely demolished. The moon had risen and we saw, in a wasted view, the panorama of the Verdun surroundings. We were on the Meuse Heights, so often noted in the communiqués of the press.

*Note: Most likely, it was Fort Belleville not Fort Souville.

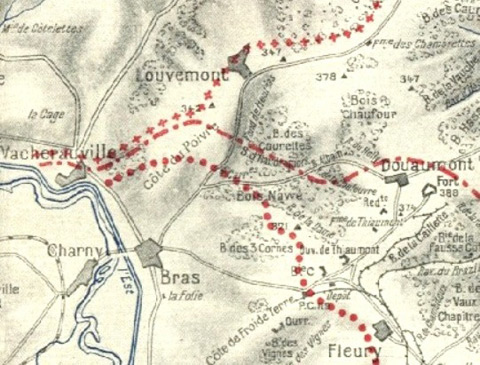

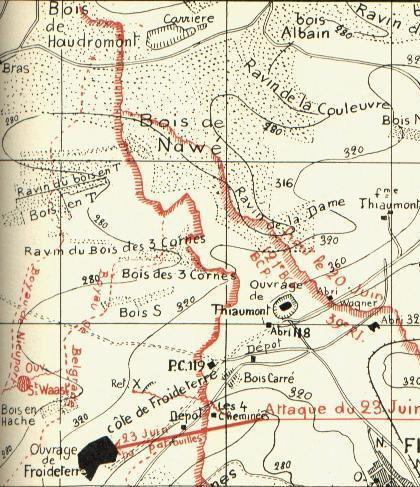

After putting our packs back on, we started our march again, with break-neck speed on the slippery snow. We descended the gullied slopes of the fort and it might have been around 5:00 am when we reached the edge of a wood [Nawé], at the top of a crest. We crossed the Ravin de Douaumont ("Douaumont Ravine")*. The fort which bears its name was located about two kilometers from us. We kept it on our right. While descending the crest, we had to pass through the wood quickly, for the Germans, detecting a relief, began to rain shells down on us. Fortunately, we only suffered a few losses in this passage. At the bottom of the ravine, an awful sight awaited us. Frozen bodies of horses here and there, emitting, despite the cold, an unbearable odor. Human bodies, among this sad debris of animals, were sprawled out all around (stretcher-bearers still hadn't been able to pull them out). They were, as we learned, the dead of the day's before fighting.

Note: Officially, this is the Ravin de la Dame ("Lady's Ravine"), although it was renamed the Ravin de la Mort ("Death Ravine").

We pass through this dangerous zone and go into position in the first line on the Côte du Poivre ("Pepper Hill"). We relieve a regiment of the 11th Corps. In front of us, barely a hundred meters away and a little to the right: Caures Wood*. The trenches that we occupy were shallow, so we were put to work upon our arrival to better shelter us from bullets. At dawn, our 75s and our heavy pieces began bombarding the enemy lines. The Germans responded immediately with a violent fire: the "stewpots" ["heavy artillery shells"] fell close by. This artillery duel lasted for about two hours. A German machine-gun fired on us (from the Douaumont side) taking the top of our trench by enfilade. We also couldn't move without immediately having a shower of bullets toss the earth near us. Around noon, we witnessed an airplane duel. We experienced a great new-found joy when, after a moment, a Taube nose-dived and fell in flames. Our first day had passed pretty calmly. At nightfall, we continued to repair our trenches in a way that, by around 1:00 am, we no longer feared being taken by enfilade.

*Note: In fact, the regiment took up positions near the Carrières d'Haudraumont ("Haudraumont Quarries") and Nawé Wood, which are located just to the southeast, and near the base of, "Pepper Hill." Most likely, the forest that Laporte sees in front is probably Caurettes Wood (part of the larger Haudraumont Wood), not Caures Wood, which is several kilometers distant.

March 11

At 2:00 am, I left with two comrades on a reconnaissance patrol in front of our lines in order to know the approximate emplacement of the German advanced posts. We crawl carefully in the greatest silence. The ground was frozen and made moving about very difficult. We skirted around a partially destroyed wire entanglement. We stopped to listen in the shelter of a light fold of ground. The thousand noises of the forest, especially at night, hindered us from hearing well. We set off after waiting a bit. About ten minutes had elapsed when, a dozen meter in front of us, two or three shadows emerged from the ground. They were definitely Germans, coming out of a look-out post. Or were they really preparing to do the same as us? We clasped tighter onto our gun stocks, without making a movement, ready for anything. After a moment, the shadows seemed to evaporate. Without a doubt the look-outs from one of the "small posts" that we were assigned to locate. We remained the necessary amount of time in order to be able to mark the emplacement.

We were preparing to turn back when the sound, barely perceptible, of weapons clinking, reached our ears. In fact, one of the occupants of the German post crawled off toward his lines, located a few meters behind. We saw him get up and jump into a hole (their trench without a doubt). Right away, we distinguished upheaved earth. Now we knew where the German first line was in front of us. To mark the emplacement that we leave behind, we lay out with the greatest possible precision, two branches in a cross on the edge of the fold of ground. After we are certain that our landmark was visible, without losing any time we made an half-turn and continued back toward our trenches flat on our stomachs. All went well. Our comrades, who were watching for our return, were happy to receive us safe and sound.

I immediately recounted my mission. From our trenches, we could see very clearly our two branches: the moon illuminated the ground like it was day. We had been lucky that the sky was obscured by clouds during our reconnaissance. Identical reconnaissances had been carried out in the whole sector throughout the night with success. The night ends calmly, but it wasn't the same on our right and left. A violent bombardment was raging. We had received very severe orders to be vigilante. The reconnaissance patrols had succeed every night, as well. But the Germans didn't seem too interested in our "Pepper Hill" sector. From the Douaumont side, to which the fort from a bird's-eye-view wasn't more than about a kilometer from us, was no more than a cloud of jet black smoke, produced by the bursting of huge heavy caliber shells.

March 13

For two days, we have not received any rations resupply. The fatigue parties can't make it through the German barrages which are unleashed without stop behind our lines. Their plan was easily understood. They planned to isolate each sector in order to puncture holes on each side, through the Bras Ravine and our "Pepper Hill" position. Our meals were made up of our reserve rations, which little by little got smaller. Already, our wine and water provisions were exhausted.

Around March 20

The days and nights go by in the same atmosphere. We were on our tenth day. During this lapse of time, we were twice able to receive some meager provisions. About the eleventh day, we went down into reserve, in the bottom of the ravine, near the 1st machine-gun company. I meet Captain Antoine, [machine-gun] company commander, and he immediately warms up to me. In civilian life, he exercised, if my memory serves me, the job of high-school headmaster. He was lacking a proper fourrier ["quartermaster"] and urged me to accept a transfer to his company. Since I was always a supernumerary in the 8th Company, I accepted happily. That same evening, I received my transfer to the 1st machine-gun company. I therefore transfered into the 1st Battalion.

I discovered Argonne vets in this company and was very content. I took up my old line of work as a liaison agent again, like in the old days (a line of work filled with risks, out in the open, but very exciting). I had three men under me. I quickly caught up on things and made acquaintances with my new comrades who are all nice. during our time in reserve I had a shelter for my three liaison agents and me which sheltered us from the rain. My captain moved around a lot in the sector and I was assigned with accompanying him in order to take in the terrain, sight the machine-guns fire zones. These functions pleased me enormously: dangerous but full of excitement!

The twelfth day since our arrival at "Pepper Hill." As we've only been resupplied very irregularly, due to the incessant German artillery barrages carried out on the crest behind our positions, volunteers must be called on to make the resupply fatigue. For forty-eight hours, we've had nothing to eat. I asked the captain to allow me to go in the evening. I gathered up six volunteers: a very small batch because of the losses we suffered every day and night from the bombardments, but sufficient enough. Around midnight, we set off walking with each man carrying, in addition to stew-pots, ten to eighteen one and two-liter canteens on his back. At the departure time, except for some bursting shells here and there, the sector was calm up to the moment when we arrived at the bottom of the ravine. There were an hundred meters of exposed ground to cross. This distance had to be covered at a lively pace, one at a time, in order to avoid being spotted by the German observers at Douaumont. The moon was out, lighting everything up like it was daylight. A rain of shells, big and small, fell down with an incredible noise in the ravine. We waited lying down for the hurricane to pass.

After about a quarter hour, the bombardment stopped. Shells continued to fall but with less intensity. I started off again in the lead, crossed the zone safely and waited for my comrades. One poilu passed through, then two, then three, four. We waited almost five minutes for the fifth. He finally arrived, collapsing next to us, very pale. His comrade had been killed instantly by a shell fragment that smashed his head. My first resupply fatigue had started off badly. Our fifth comrade got back on his feet very distressed, still shocked from the sight of his unfortunate campanion. A moment of respite. We started off again and reached the crest an hour later, without another incident. We then descended the slope of Bras Ravine*. We walked another hour across the shell-holed ground. We couldn't go very far along the route in an hour. We made out a gathering behind a fold of ground: it was the field kitchens. I gave the head-count of my company to the resupply chief and the distribution commenced right away.

*Note: Bras Ravine can not be located on any maps. It is quite possible though that Laporte is describing the Bois des Trois Cornes ("Three Corners Wood") Ravine, which best fits his description.

Some comrades from other companies had left already. Our canteens and stew-pots (beef and beans, very appetizing) filled as well, we rested for about ten minutes, for it wasn't a good idea to depart all at the same time on such a clear night. German shells fall continuously in the plain. After having drained a hot cup of coffee, we left again for the trenches, one behind the other. The explosions had gradually come closer as we approached the last crest to pass over before getting to the Douaumont Ravine ["Death Ravine"]. We paused several minutes on this crest, for remember, the hike through the mud, in shell-holes, explosions here and there, the weight of the canteens on the back and two stew-pots in each hand, it wasn't exactly a walk in the park. Masked by tree trunks, we rested for a moment, motionless before setting off again towards the ravine. The barrage fire was less violent than during our departure. Fortunately, for on the return it wasn't possible to run with our load.

The ravine was crossed without hindrance and we arrived in the trenches at 3:00 am. All our comrades welcomed with joy. The coffee, still warm, felt good in all these poor stomachs subjected to such tough ordeals. The rations distributed to everyone, I went back to my shelter and, before eating, broken by fatigue, I rolled myself up in my blanket and fell asleep. The shell blasts both near and far didn't disturb me.

Around March 23

Around 6:00 am, I was awoken from my slumber by an intense fusillade. Our machine-guns were in action. I ran with my captain and three liaison agents to our trenches on the top of the hill, about 50 meters away. The Germans were making a sortie. I made sure my revolver was ready to fire (my rifle had been replaced by this weapon because of my functions) and picked up a rifle which I loaded immediately. The first grenades were exploding not far from us. Our artillery opened up with an intense fire on the enemy trenches. Our machine-guns fired continuously. The Germans didn't make it closer than 20 meters from our lines and all those who left their trench never made it back. Their attack had failed. They had suffered heavy losses; the number of bodies that could be seen, piled up in front of our lines, testified to this. All day long, their shells fell on our positions. We only took very light losses on our side and we were able to carry out an ammo resupply for our guns without incident. [. . .]

Around March 30

In the evening of the twenty-first day here, around March 16 to 19 [really the 30-31], we were relieved. Our departure from the trenches was carried out without losses, so to speak. For several days, the Germans had given up their barrage fire on the ravine. Their shells rained down on the rear areas in the suburbs of Verdun. On our left, there was no less than a continual rolling of explosions. The Germans were attacking Hill 304 and the Mort-Homme, which were positions located on the [left] bank of the Meuse. Once again, we passed in front of Fort Froid-Terre. Shells fell thick on our return route, on each side disemboweled horses emitted a pestilent odor. Artillery caissons embedded here and there in the water-filled shell-holes. Under the shells, we suffered some losses before arriving in Faubourg-Pavé (the name of a Verdun suburb [on the north-east boundry]).

Around April 1

We spent the day housed in the large buildings of the town. There, we were set up like kings, where we recovered a little energy. In the evening, after an hour's march, we were loaded up into trucks which brought us to our rest point at Blaircourt [today spelt Blercourt, it is about 8 km southwest of Verdun]. We arrived there around 5:00 am.

Around April 2

Our billets, comprised of well-prepared tents, stood on the hills commanding the village. Troops everywhere! Our regiment, pretty exhausted, had to reform itself. We waited for reinforcements which weren't late in coming*. In fact, after a week spent in this setting, our companies were pretty much at full-strength.

Note: These were composed almost entirely of new recruits from the class of 1916, 18 and 19-year-olds.