Campaign History of the 151e Régiment d'Infanterie - XIII (Part II)

~ 1916 ~

Verdun - Second Tour (9 April)

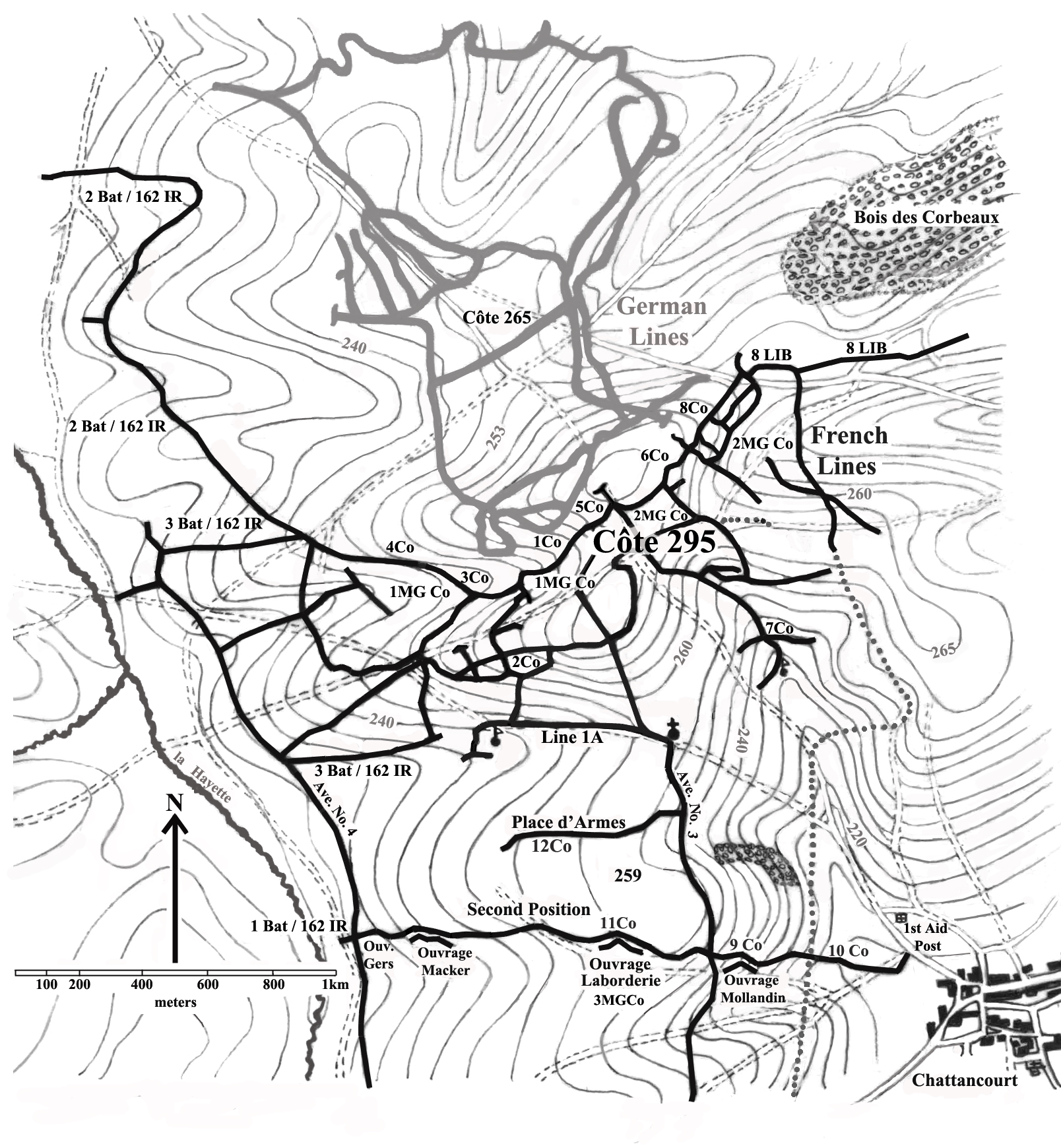

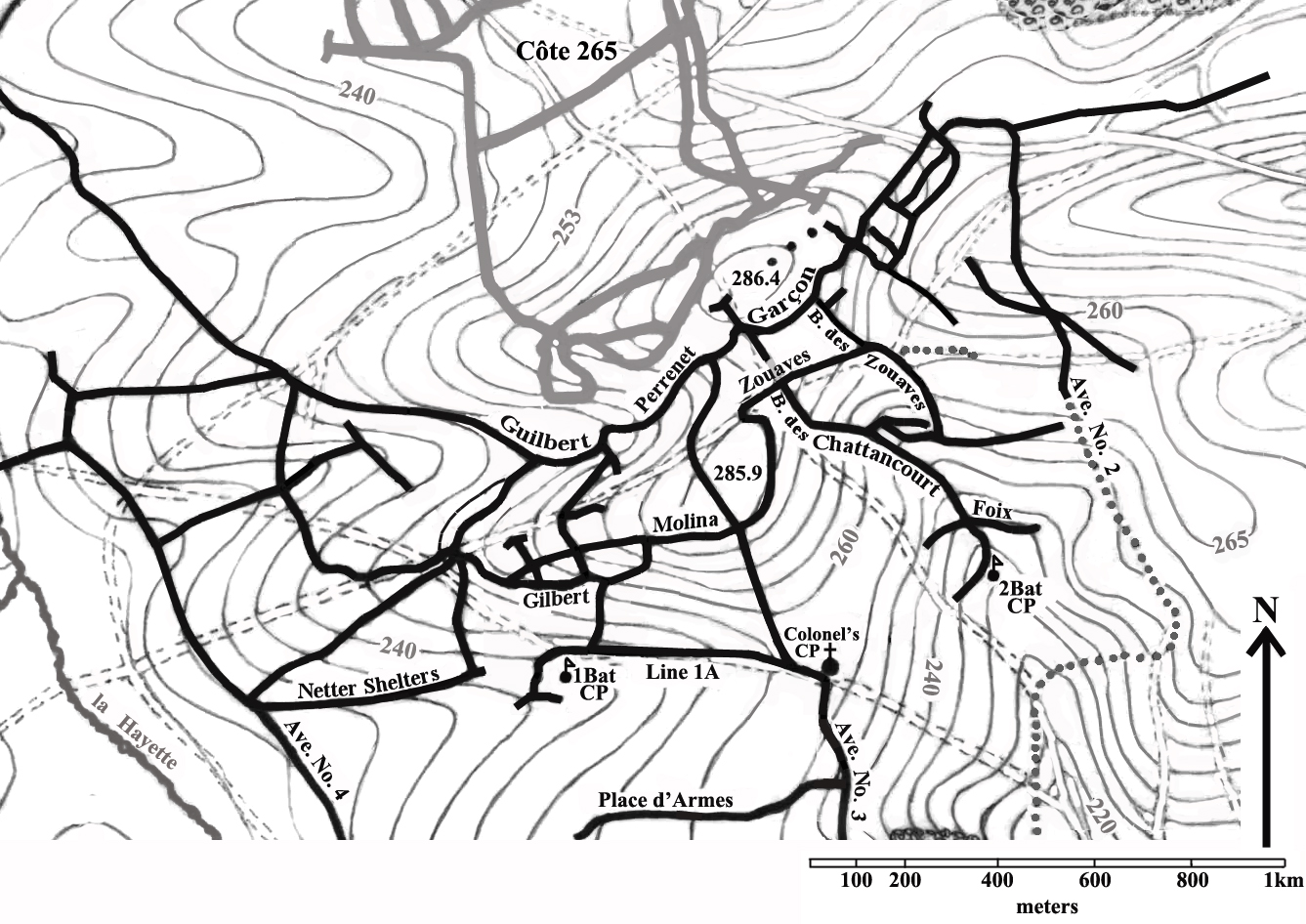

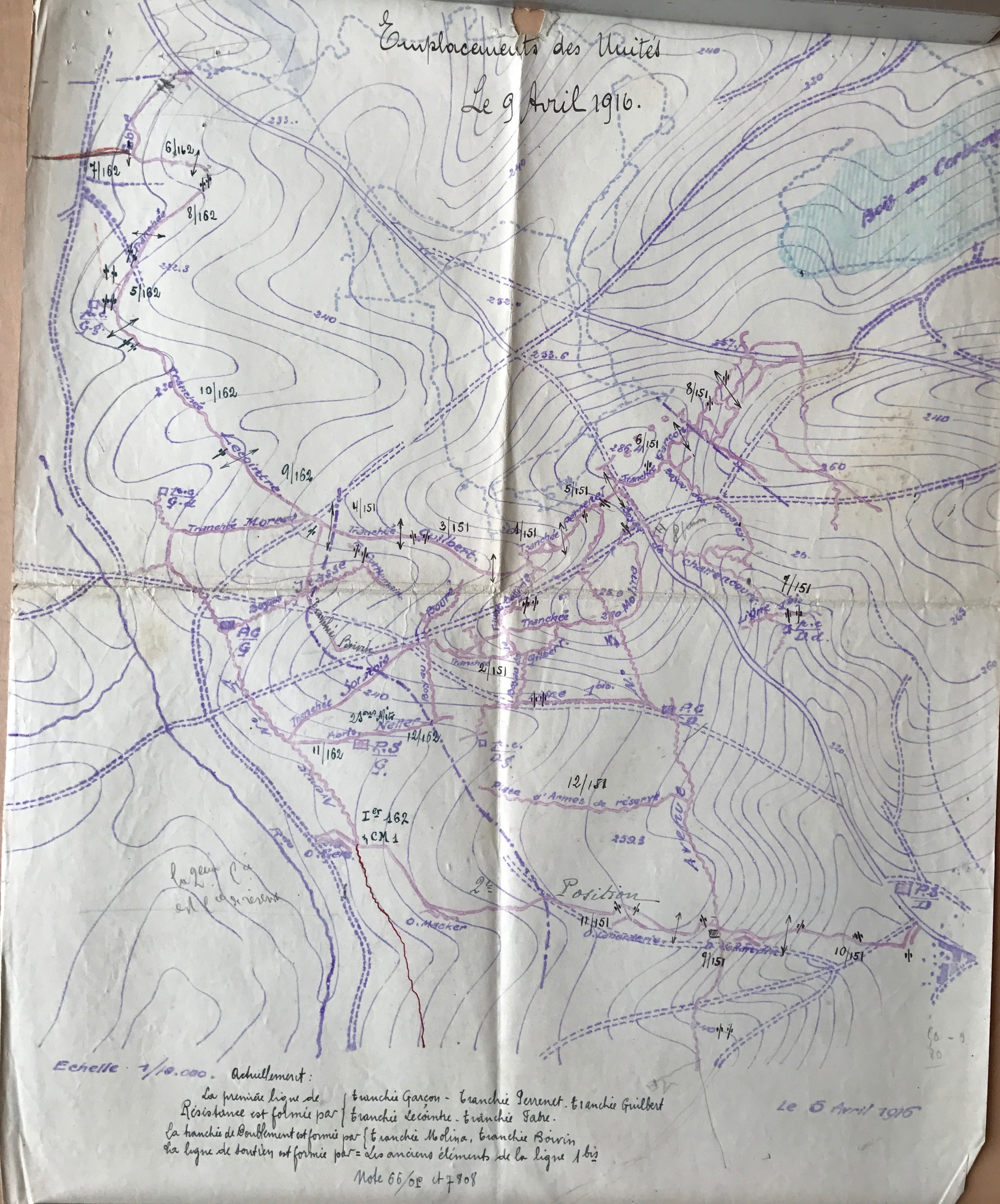

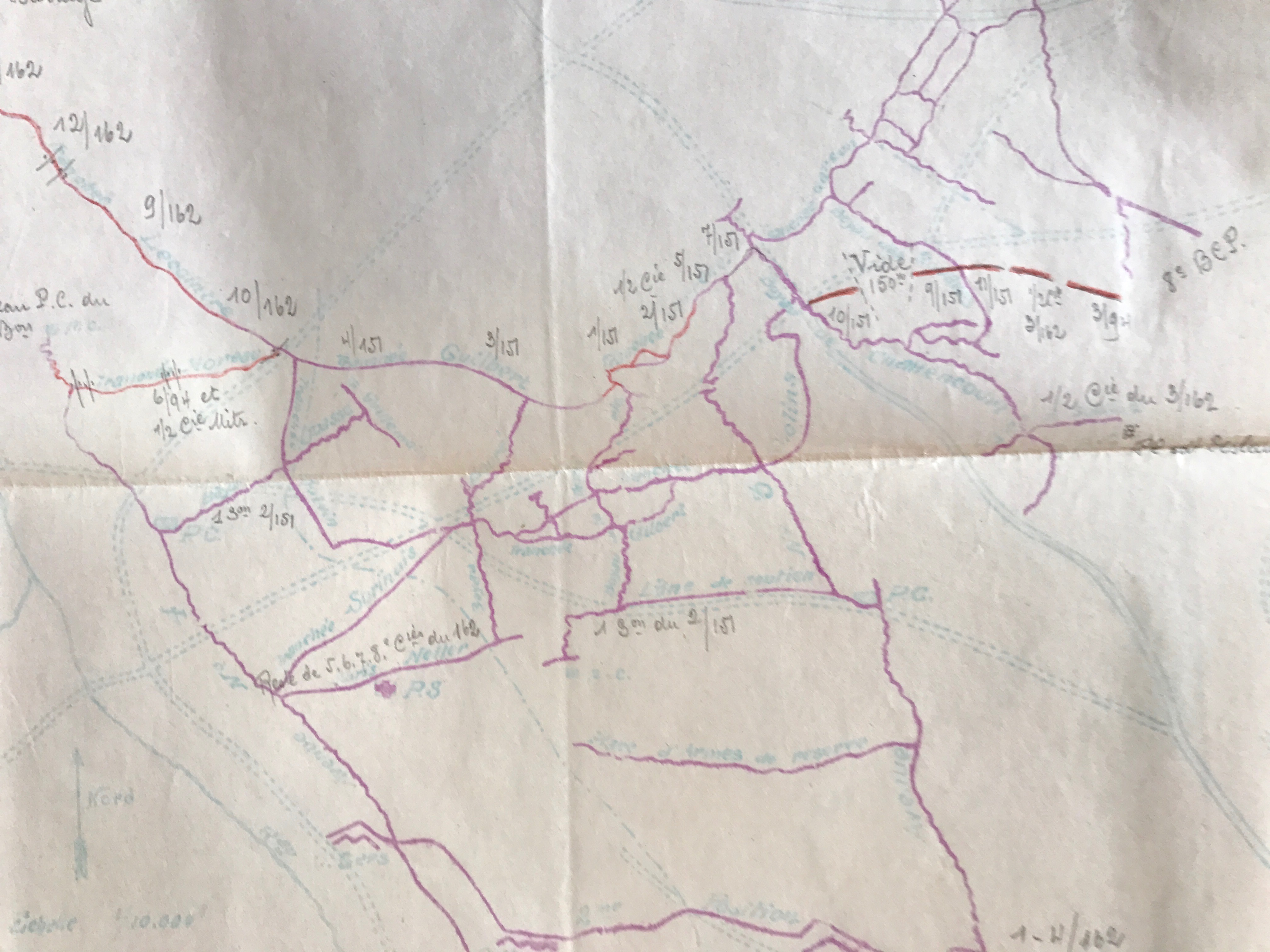

Left: map of Mort Homme showing the disposition of the 42e DI on the morning of 9 April 1916 (drawn by John Bracken). Center: map showing the entrenchments on the summit of Mort Homme. Right: the disposition of the 151 on the morning of 9 April 1916 (source: 42e DI archives).

9 April: The early morning remained calm. As he woke, Jubert gazed at his slumbering men: "They were sleeping, with no suspicion that death hovered over them. Like condemned men, they would only be awoken in order to die." At 0700 hrs, the German artillery opened up with a massive bombardment on Mort-Homme and the neighboring Hill 304. In fact, it was the heaviest one since the opening of the battle on February 21. So as to feign ignorance of the impending assault, the French artillery, contrary to the normal practice, fired only a few number of shells and far away from the interior of the German lines. All units in the 42 DI were on high-alert and the troops were all at their combat posts, waiting and ready. Campana was sitting in his newly expanded advanced post with his section. He had already ensured his men had their rifles ready and placed stockpiles of grenades within arm’s reach, and then waited.

As the sun rose, the day revealed itself to be clear and the sky free of clouds. Suddenly, at 0800 hrs as anticipated, a single 105 shrapnel shell burst in the air, producing a yellowish-green cloud of smoke and breaking the serene calm. It was the signal for the attack. Three more shells burst, one after the other, while on Côte 304 huge plumes of smoke burst out of the ground. Innumerable shells now roared overhead. At Chattancourt, a veritable storm of 150s plummeted down. Then from all around, columns of smoke – black, gray, white, and yellow – shot up from the earth as the general bombardment of the entire sector began. The ground under our feet shook as hundreds of shells detonated around them.From the sheltered position of the second-line positions, Jubert watched the spectacle unfold.

There were two distinct zones of fire: one smashed the trenches along the line of Côte 304 to 285 [really, 295 of Mort Homme], the other blocked the Colonel's ravine [Ravin de Chattancourt at the base of 295] where the enemy judged our reserves to be built up.The JMO states that the positions of 1 Bat. (on the left) began to be heavily bombarded at 0830 hrs. The storm of shells continued unabated for another three hours. The bombardment then doubles in intensity around 1100 hrs with shells of all calibers. Meanwhile, 2 Bat. (on the right) came under an even heavier bombardment than 1 Bat. The 7 and 8 Cos. (on the right flank of 2 Bat.) was particularly targeted by heavy minenwerfers. Campana could see both companies from his position and counted the shells coming down on the 7 and 8 Cos. positions at the rate of five a minute. Meanwhile, behind him, eight shells exploded nearly simultaneously in the trench he had abandoned the night before. A close escape indeed. To his right, he could see heavy plumes of black smoke rising up into the air – the Germans were using flame-throwers against the chasseurs of the 8 BCP, turning the men into living torches. Meanwhile, in the skies above, German aircraft were very active, reporting back to their artillery the effects of their fire. One of these is shot down by a French Nieuport and crashes down in the French lines, the pilot burnt to a crisp.I have rarely seen such a sight. It was massive in scale and had a life of its own. It spread out like a game of death in the beauty of the morning...Brushstroke was being added to brushstroke in quick succession, dozens at a time. So heavy you could suffocate if you were close. From a distance they looked fresh, harmonious to the eye. Thunderclouds floated across the sky, touched with the color of the morning. The sun has this virtue: beneath its rays, death takes on pure beauty.

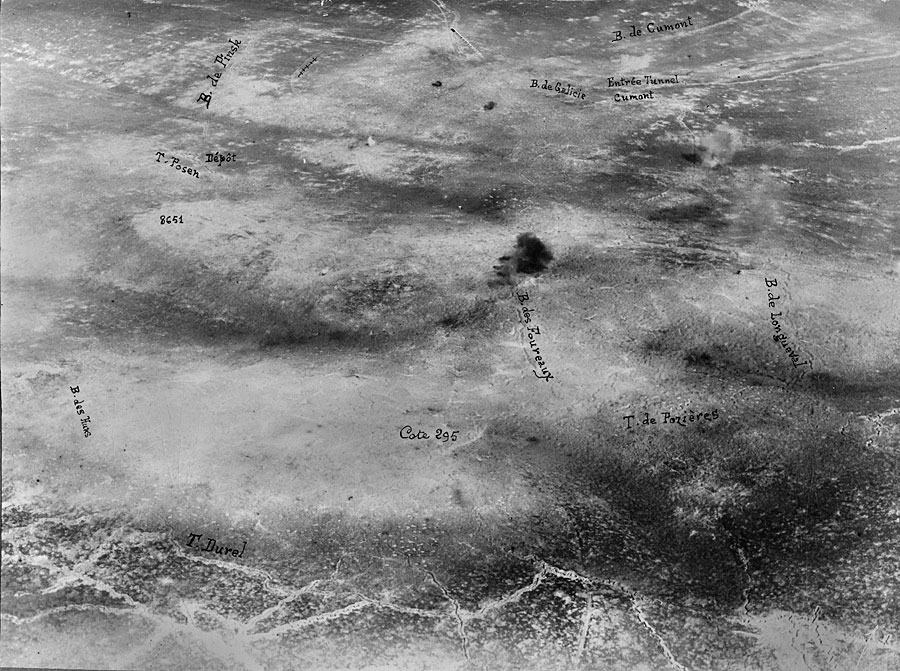

Le Mort Homme under bombardment as seen from the air and a view from the top of the summit with human remains in the foreground. The center photo is another view of Mort Homme looking north east. Source Musée de l'Armée.

At noon, the German artillery lengthened their fire and the bombardment achieved its maximum ferocity, the sound of the explosions now changing into a demented confusion of noise. A flare shot up from the German lines. It was then that the German infantry assault began. (Note: While Campana and Laporte said that the German infantry went over the top at 12 on the dot, the JMO states it was at 12:15). From his advanced post with its commanding view, Campana recorded the scene:

Suddenly, waves of German infantry now jumped out of their trenches and rushed forward toward our lines. A company of German infantry with bayonets fixed now charged against Campana’s position. It pressed on a few meters, then, under the tac-tac of our machine-guns, it collapsed. Some men having escaped our volley of bullets fled back in disorder towards their jumping off positions. None made it back. Our merciless fire stopped them in their tracks and the survivors threw themselves to the ground.Laporte was also a witness in the first-lines and recorded the scene:

They were all superb, strapping fellows. When this mass of men in tightly packed ranks had gone a dozen meters, the cross fire of our machine-guns literally mowed-down the first ranks. The second wave then took its turn and immediately suffered the same fate as the first. Those Germans, and there weren't many, who managed to pass through this storm of metal were taken down by rifles or grenades.The situation was far more critical though elsewhere on the regiment's front. On the right, other waves of German infantry broke against the 7 and 8 Companies, whose trenches had been pulverized by the well-sighted heavy artillery fire and could not be adequately defended. Campana could see them clearly.

Gunner-Sergeant Dufour pointed his weapon on the teeming horde: the Hotchkiss spat out 300 bullets a minute. Under the rain of steel, the Boches tumbled down like toy soldiers and in a few seconds, many green-gray bodies lay scattered on the ground. Seized with panic, the survivors scattered in all directions. So each of my men chose his victim and did his best to knock off another pretty target. Not a single German made it back to his trench. In front of us, a calm settled in, but to the right and left waves of enemy advanced toward our positions and on the side of the 8 Chasseurs, the hideous black smoke continued to rise up.With the 1 MG Co., Cpl. Laporte was awestruck in the face of the fury of the fighting.

What an inferno of fire! What an infernal noise! The unending German waves were all made of tightly packed ranks. They gradually grew larger. Heaps of bodies were already laid out in front of us. The muzzles of the machine-guns turned red. We fired without stop. From their part, our 75 canons created enormous devastation in the German trenches, just behind the assault waves. Our heavy artillery rained down on the German reserves without stop. The Germans continued to fall in front of our lines. It was a real slaughter...Savoring the carnage unfolding before his eyes, Campana couldn’t help but think back on the 6 October 1915 in Champagne, when the 151 had been slaughtered in the impenetrable barbed-wire. Though few of his men had been there with the 151 and escaped the massacre, Campana told his men about the disaster and inspired a deep abiding desire for revenge.

Angrily, hatefully, but with calm, they chose their prey. Rifle placed in the crook of the elbow, attentive, they scan the slopes covered in dead bodies. Under our violent bursts of gunfire, many Germans were pinned to the ground, hoping to escape the massacre by playing dead. But sometimes, either taken by a sudden panic or profiting from a moment of calm, they leapt up and ran back towards their trenches. Amused by this new type of hunt, my men took carefully aim and shoot them down like rabbits.Recovering from the shock, Campana could now see the German communication trenches that led back to the enemy’s third line teeming with little green men, like branches of a tree: it was Prussian chasseurs. They were over 1,000 meters away [on 265] and likely thought they could not be seen by the French, as many marched across the open ground in order to move up quicker. They Prussians advanced carrying their rifles in one hand, their bayonets reflecting the sunlight. Campana ran over to the corporal-gunner manning the nearby Hotchkiss of this excellent target and then rejoined his men. Once again, the machine-gun spat out its bullets by the hundreds and the men see a great agitation suddenly produced among the enemy columns. The German chasseurs quickly jump down into their communication trenches but the storm of bullets contains to rain down on the tightly-packed enemy troops.I had taken the rifle of my orderly and see a big German hurtling down hill 265. I fired in repetition. On the third shot, he threw up his arms and collapsed with his body stretched out. I continued to empty my magazine on him. Out of the six rounds that still remained, four hit his body, the other two throwing up little clouds of dust behind him. I was certain that he was truly dead.

Boche planes overhead look down on us. A few moments later, a volley of 105s and 210s slam down around us. My soldiers jump down from the fire-steps. In order to give them confidence I remained at my post and photographed the explosions. I was thus able to take one of a fantastic explosion of a 210, a fragment of which struck my chest but didn’t have enough force to penetrate.

"Get back up to your places, the Boches are going to come back at us again. We don’t have anything to fear from the bombardment, these shells aren’t for us."The Captain [Carrère] arrived in the trench. He was tranquilly smoking his old pipe:

"How’s it going in front of you?

"Not bad. See for yourself.

"Oh, hey, that’s nice work. I’m coming from the 3rd Section. They already have three killed.

"For the moment I don’t have any killed or wounded.

"Gontran has had his second machine-gun buried by a 105.

"He’s doing marvelously. Look at this whole line of Boches it took less than two minutes to mow down." The Captain advanced toward Sergeant Dufour to congratulate him:

"It's a pleasure to see that you haven’t wasted any time!

"The pleasure is entirely mine, mon Capitaine. It’s fantastic stopping these bastards right in their tracks and to see them come tumbling down like chips of wood. There was an officer leading them, making big gestures with his arms to give his men nerve. I shot him down with my musket. He must be over there, in the group of dead. I’m going to try to find him with my binoculars…I see him, hold on, mon Capitaine, would you like…"A dry crack rang out and Dufour collapsed into my arms, his skull split open. The bullet striking him square in the forehead had burst his head open and bits of brain splattered our greatcoats. The sergeant had been knocked off.

Suddenly a loud explosion rings out to Campana’s right and a corporal comes running up to him.

"Mon lieutenant, the 210 fell close to us, the machine-gun is in pieces, the aimer and loader have been killed. I’m done for too.After calling over a stretcher-bearer to take care of the wounded corporal, Campana tells his men to fire as if they’re at the shooting range, with calm and taking care to not waste ammunition. They had already gone through an entire sack full of cartridges and they’re muzzles were burning hot. Yet with their machine-gun out of service, the 30-40 bullets that the rifles could fire a minute weren’t enough to stop the rapidly advancing German troops, which moved across open ground and up through the communication trenches before deploying into the departure parallels before throwing themselves forward.

"Are you wounded?

"I am in the chest, I’m f-cked."

My men fired without stop and each time they knocked off a Boche, they laughed like a big children…I carried out target practice for more than a quarter hour, while my orderly reprovisioned his comrades with ammunition. I’d hoped that our artillery fire would open up on them soon, but their fire appeared to be concentrated to the right where the Prussian chasseurs had taken the [French] first-line and were moving on to the second.There was a new lull in this part of the sector. But from Cumières side (to the east), the bombardment continued to rage on. For his part, Laporte watched the progressive destruction of his regiment and the bravery displayed by so many.In front of us the Boches came at us but en masse this time. In a few minutes the slopes of hill 265 were covered in enemy rushing toward us. This time, we only had our rifles to stop them, and that was not sufficient. At our feet, in Lieutenant Olivier’s trench, the fighting was already hand-to-hand. On the off chance, I sent up a red flare to request artillery fire. The situation had become critical. The green horde had already overwhelmed our first-line and was advancing toward us…Suddenly a terrifying barrage was unleashed on the German waves: the 75s and 155s rained down as thick as hail on the hundreds of men packed elbow to elbow. My soldiers screamed in joy while the fire continued.

"Bravo! Bravo!

"Go on then! Bing! Bing and bing! Oh, mon lieutenant, take a look at this omelet!"The bodies were piling up, whole lines of Boche were dropping like wheat before the scythe. Others under the explosions of our shells were thrown several meters up into the air mixed with clouds of earth and stones before crashing back down. German grenadiers, with greatcoats rolled around them in bandolier fashion, advanced toward us. Barely thirty meters separated us from them.

"Fix bayonets! Get the grenades ready!"

The fire of our 75s redoubled in intensity. Fortunately one gun fired too short and several shells fell on the enemy grenadiers. Seized by panic, the survivors tried to about-face but in the violence of the bombardment, they ran around lost. So they made the "Kamerad!" [to surrender] and headed toward us. There still were about forty of them. We were too overexcited to have pity on them.

"No prisoners, boys! Shoot all these vermin!"

Caught between our rifle fire and our bursting shells, they ran panic-stricken to the right and left. My men cold-bloodedly shot them down. Soon…the last grenadier collapsed. For the second time the enemy fell back in disorder. Heaps of corpses lay on the slopes of hill 265. It looked like a field recently harvested where bales of hay wait to be collected.

One of our sections had lost all of its men except for one, Faglain*, who was able to save his machine-gun and continued to fire into the enemy waves. We took some losses, but nothing compared to the bloodshed across from us. Thousands of their men were stacked up one on top of each other in front of our lines, the ones further off were countless. Further away, the Meuse carried along streams of bodies. We (those of us who survived) looked like filthy chimney sweeps after this terrible massacre. They didn't think much of their assault troops, sacrificing countless men. Our losses were less severe than theirs.

*In fact Soldat Faglain's actions are cited in the official regimental historical: "...[T]he sole survivor of his machine-gun section and with an extraordinary calm, he set his gun up on the parapet and coolly mowed down the enemy columns which, after several attempts, fled back in disorder, holding them off for two hours until a bullet arrived felling him across his gun."

On 2 Battalion’s front, the situation had continued to deteriorate. Around 1300 hrs, under the weight of the German infantry attack, 7 Company is no longer able to hold onto their trenches and falls back creating a gap between the 1 and 2 Battalions. Meanwhile, the 5 and 6 Companies fight desperately to hold onto their own trenches, as waves of German attack troops begin to overwhelm them. Gradually they begin to cede ground to the enemy. Effectively, all companies in 2 Battalion (5-8) had now been pushed out of their first-line positions. Further down the line, the 8 BCP, which was in liaison to the right of 2 Battalion, had been forced to abandon its first-line too. This resulted in a large gap opening up between the 8 BCP and the 151's right flank, a precarious condition that could be disastrous if exploited by the enemy.

As the German assault troops signaled back their progress, German artillery largely ceased firing to avoid hitting their own men. Below the summit in the second-line, Jubert and his 11 Company remained largely out of touch with the events going on above them. They took the slackening of the enemy’s fire to mean that the attack had been thwarted. Believing they had been spared, the men vented themselves in hysterical relief. Soup was served to the men who feasted voraciously. As the smoke overhead began to clear and suns rays began to break through once again, the men sat down to play cards as they awaited further orders. Jubert was doing quite well for himself with a lucky run of cards when a message arrived from the battalion commander, which quickly blew away the false-pretense of comfort like the arrival of a 77 shell. The top of Mort-Homme had been overrun and they were ordered to retake it immediately. The prospects seemed dire indeed. They would be counter-attacking uphill against an enemy who was quickly entrenching in the newly conquered positions. To make matters worse, Jubert and his men would have to advance across open ground, as navigating the communication trenches up the slope would only slow their progress.

The counter-attack to retake 2 Battalion’s positions would be led by 12 Company, together with the remnants of 5 Company and two sections of 7 Company. From his post, Campana could see the units moving up the communication trenches to the second-line positions back to his right. They were composed largely of new recruits of the class of 1916, which had only joined the regiment two weeks before, now about to face their baptism of fire. Campana took out his binoculars and recognized a classmate from his Saint-Cyr promotion class, Sous-Lieutenant Camusat de Riancey. Suddenly Campana was struck by a small detail and could hardly believe his eyes. His classmate was wearing his white dress gloves!

French 75s rained down now with their high-pitched screams on the regiment’s lost first-lines for several minutes to soften the enemy’s defense before lengthening its fire. As it did, the counter-attack force, bayonets fixed, jumped up out of their trenches and bounded forward in two waves. Observing from his position above and to the left, Campana watched his Saint-Cyr comrade climb out of the trench only to immediately collapse on the parapet, already struck by a bullet. Taking a moment to recover, he got back up on his feet and ran another dozen meters before being struck a second time and falling down again.

Ahead of him, his men rushed upon the enemy defenders. Between the brief moments of silence punctuated by explosions, Campana could hear singing as the attackers closed in. Here we encounter one of those great incidents of war that has become ensnared in the murky reality of myth. Campana claims that he heard the sound of the "La Marseillaise" being sung. Many official accounts at the time reported the same. The French Etat-Major along with the Press seized on these reports, trumpeting them around as a display of the patriotism and zeal of French troops. The reality is probably something different but no less compelling, as will be recounted later by Jubert.

Many of the men in 12 Company by now had been shot down. Those who made it to the objective now jumped down into the trench and for several minutes a short but brutal hand-to-hand fight ensued. Soon the remaining Germans fled the trench, pursued close behind by the French attackers and their now bloodied bayonets. Few in number, the survivors of 12 Company pulled back to the retaken line.

Looking back at the spot where his friend had fallen, Campana could see Camusat de Riancey lying motionless upon the ground, his white hands resting crisply on his blue greatcoat. He would learn later that evening that his young friend had not been killed outright. Thrown to the ground by a bullet that had torn open his side, he had the strength to get back up again and continue to lead his men. But he was struck by three more bullets in the belly and collapsed a final time. Transported back to a first-aid post, he would die in horrible agony late in the evening.

Despite their valiant efforts, 12 Company was unable to reestablish contact with the 8 BCP on the right. Around 1420 hrs, the remnants of 5 and 6 Companies were enveloped by the enemy and largely wiped out. Shortly thereafter, 11 Company received orders to prepare to counter-attack to the right of 2 Battalion’s positions where 12 Company had advanced in order to reestablish contact with the chasseurs. Sous-Lieutenant Jubert helped to assemble his men, noting that at the moment there were only a hundred or so men present in the company.

Despite the seriousness of the situation, Jubert saw no hesitation his men, many of whom were the 20-year-old recruits of the Class of 1916. As soon as the order was given by a sergent, the men went about quietly collecting their gear and loading up on extra rations and ammo. As soon as they are all kitted up, the company moves forward through the communication trench to the jumping off trench in the second-line. Based on Jubert’s account, the 11 Company likely advanced in a northeasterly direction toward 2 Battalion’s lost first-line trenches stretching to the east of Mort Homme. Up on the erupting summit of 295, isolated handfuls of survivors from the 5, 6, and 8 Companies held onto the small holes and folds in the ground that now comprised the French first-line. Following another preparatory artillery bombardment, at 1545 hrs 11 Company sets off to retake the positions lost by 6 Company.

Climbing out of the trenches, they quickly formed up into well-aligned skirmishing lines and began to advance up the slopes of Mort-Homme. The majority of the men's faces were grave, though some managed a pale, taught smile when Jubert caught their eye. As they approached the combat zone, spontaneous shouts of encouragement were exchanged:

"We'll show them what the boys from the North are made of, mon lieutenant! "And those from the Ardennes too! "And the boys Paris!"As he and his men the colonel’s dugout, Jubert could see wall of fire and steel in front of them. Jubert turned to look behind himself and as he did, he saw a shell burst on the ground and hurl a man several meters into the air. As the dead man plummeted back, he was immediately jerked back up by the blast of a second shell. The same shell that tossed the ragged body back up caused a half-section to flatten itself in anticipation on the ground. Yet as soon as the danger had passed, the men rose back up from the ground one-by-one and get back into line. As the elements of 11 Co. continued forward to the bottom of the crest, Jubert saw an officer gesturing to them and he made his way toward the man. It was Mollet, who’d been posted to give last-minute directionsWe’ve taken the crest. Once there, we go down towards the ravine where, like at the bottom of a crucible, we meet a hellish fracas of explosions and smoke that dispenses death amongst us. Another hundred paces, we’re in the danger zone. The shells fall all around us. Men are getting killed. With grave faces, they move in pace and in good order.

"The Boches are up there [on the crest] or behind it. One section will progress through the Boyau de Zouaves, the rest of the company will take the crest by the right oblique.After advancing another 200 meters, Jubert and his men reach the first crest and see the second (265) ahead of them. They’re unable to spot any indications of a trench line. Jubert and the other section leaders order their men to resume a walking pace and maintain their order for the final push. They have another 100 meters to go as their eyes continually scan for the enemy. Amazingly, their skirmishing line is still intact and in good order, as the men advance with their rifles balanced in one hand.

"Where’s the enemy?

"That’s for you to tell us."Us section leaders are at our posts several paces to the front. I look at them: an admirable line to my right, Noël, Dubot, Buisson. "We’re going to give them a thrashing!" a man shouts, laughing. "The bastards won’t get past us." More voices join in, building their confidence. Laughing, I appease them and calm them down with a gesture.

"We’ll sing on our way up there! Forward, boys!" There’s a real sense of satisfaction making this assault. We’re advancing, Noël, Dubot, Buisson, and me. We maintain good order. It’s a pleasure to face death in this way.

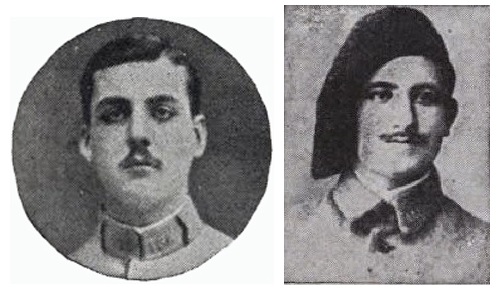

Sous-Lieuts. Noël and Buisson (KIA 9 April 1916).

Suddenly on their left flank, a German machine-gun opens up on them, which the Germans had set up near the PC of 8 Co. At this very moment, in attempt to bolster his courage, a man struck up a popular café-concert song, which soon the entire company joined in on. But the machine-gun had its own song of death to sing and men were now being struck down by its rain of lead. Jubert could hear the cries of his fellow officers, Noël, Dubot, and Buisson, as they are hit and fall but he presses on all the same.

"Watch your alignment!" I yell.The momentum of the charge had hurtled the survivors of 11 Co. to top of the hill. The singing had now stopped as eyes now fixed on the final objective that was thirty paces away, then fifteen, then five. Jubert turned around and asked himself where the company had gone to. Finally, he reached the trench and jumped down into it, but found it deserted, the enemy fled. Where were the Boches? Jubert’s men asked. Jubert quickly took count of his men. He saw a handful of his old soldiers and a few new recruits from the class of ’16 (who he’d still not learned their names) -- ten in all out of the hundred who had started off. That was it. Looking back on the ground behind them, he could only see the dead and some wounded who were trying to drag themselves up to the trench as they continued to be fired on by the enemy machine-gun.

"Forward!" someone repeats behind me, "We’ve got them!"My men follow the command. Bullets patter down by the hundreds and plow up 20 cm of earth, as a light smoke rises around me. That’s their effect on this beaten ground, as the dust rises up. They brush past my feet and graze past others as I dodge about them. Behind me a man is singing and the cries of the wounded are silenced.

In the safety of the trench, a soldier offers Jubert some fancy tobacco, which he always takes into combat. Jubert shares it with the survivors around him. In the uneasy calm, anxiety now began to seep into Jubert and his men, as the cries of the wounded and their calls for help reach their ears. To help boost morale, Jubert seized a German envelope lying on the ground and ceremoniously recorded the names of the men to recommend them for commendation for the Croix de Guerre.

A quick exploration is made of the trench system they now occupy. There’s no one there except for the dead: French zouaves and chasseurs and Germans, all mixed together. Jubert recognized the importance of the position, albeit that it was only defended with ten men, and quickly jotted down a brief note to Lieut.-Colonel Moisson: "I don't know where I am, but the position is of the first importance, and I have only ten men to hold it. I request the two companies be sent up immediately.”

Sending the man off to regiment, Jubert goes on a brief reconnaissance with two wounded comrades. Proceeding two hundred meters down a flattened communication trench, they suddenly spot an entire platoon of German infantry only twenty meters away, heading up another trench running perpendicular to their own. The Germans, loaded up with grenades, have their gaze fixed straight ahead though and Jubert with his pitiful company go unseen. After the platoon passes, they beat a quick retreat back to the center of the position.

Once arriving back to the small party of defenders, Jubert is told that the runner he had sent out was wounded and returned unable to deliver the message. A wounded fellow officer, Dudot, volunteers to go to deliver the message. When Jubert protests, the officer insists he be the one to go since he was effectively out of the fight. He shakes Dudot’s hand, the fingers already stiff and paralyzed. As he watches Dudot scale the parapet and head down into the ravine, he can’t help but think to himself, "There goes another dead man."

The small band of survivors of 11 Co. had made it to the 295 summit having taken about 600 meters of ground. As Jubert’s impromptu roll call had confirmed, of the 100 men who had begun the counter-attack only 10 were left. Most had been cut down by enemy machine-gun fire in the final portion of the advance.

Following 11 Co.’s counter-attack, at 1830 hrs the 10 co. is sent forward to counter-attack to try to retake additional ground lost by 2 Bat. This company advances in the same perfect order as as the 11 Co. had but the same enemy machine-gun that had been placed in the from 8 Co. PC and forces it to halt it's advance on the summit of 295. The 10 Co. makes a final attempt to advance shortly after once night had fallen but is unable to progress. At this point, only 9 Co. still remained in reserve in the second line.

Gradually, the German bombardment begins to diminish in intensity. Some final salvos fall on Chattancourt and at the foot of Côte 304. A salvo of yellow-green shrapnel shells burst in the sky and then an impressive silence settled over the land. The last rays of sun bathed the heaps of bloody corpses covering the slopes of Mort Homme. The sky turned a blue-green, then pale green, then purple. Above Cumières the moon rose glowing red. As it continued its ascension, the light changed to yellow and illuminated everything in a blue light.

The regiment's situation on the right was tenuous. On the regiment's right, a 600 meter gap existed between it right flank and the 8 BCP's left. There also remain gaps between 7 and 10 Co. and between 10 and 11 Cos. Meanwhile, Jubert's request for reinforcements meanwhile went unanswered and the young officer decided to try to reach the regimental PC himself. He struggled down the ravaged, shell-hole strewn landscape, scrambling up and down endless craters. In one large crater, he encountered a group of wounded, among whom is Sous-Lieut. Noël whose leg has been broken. Noël pleaded with Jubert to take him with him. It wrenched his heart to leave his friend but his first duty is to get to the colonel. Jubert pressed on but encounters a group of stretcher-bearers and directed them to group of wounded he's just left behind. When he finally arrived at the colonel's PC, Jubert was greeted like a man returning from the grave and was showered with congratulations. Sous-Lieut. Coureaux (flag-bearer) informed him that both General Deville and Lieut-Colonel Moission had observed his company's counter-attack and were brought to tears at the moving sight.

Yet to Jubert's call for reinforcements, there was none to give. After some further discussion, eventually Jubert is promised that a company will be sent up as soon as one is available. Dejected, Jubert headed back up the hill and on the way passed Sous-Lieut. Noël being carried back on a stretcher and who'd grown very pale. The two embraced without speaking, his friend's fate all too obvious: death was taking another life. When Jubert arrived back at the summit, he found his men still nervously holding on to their position, though it comforted him to see them eating their reserve rations of bread and tinned meat.

Shortly after, Jubert would go out on reconnaissance with one of his men, stumbling upon the dead in front of their trench. Fortunately, he was able to find the battered remains of the 8 BCP and reestablish the liaison between the two units, albeit tenuous. All along the line, the battle-worn exhausted men of the 151 waited vigilantly through the night fully expecting another German attack, but it does not come. Nonetheless, Jubert and his small handful of survivors of 11 Co. would be left to hold on to their dearly-earned positions for 36 hours without any relief, all the while under non-stop artillery bombardment and machine-gun fire.

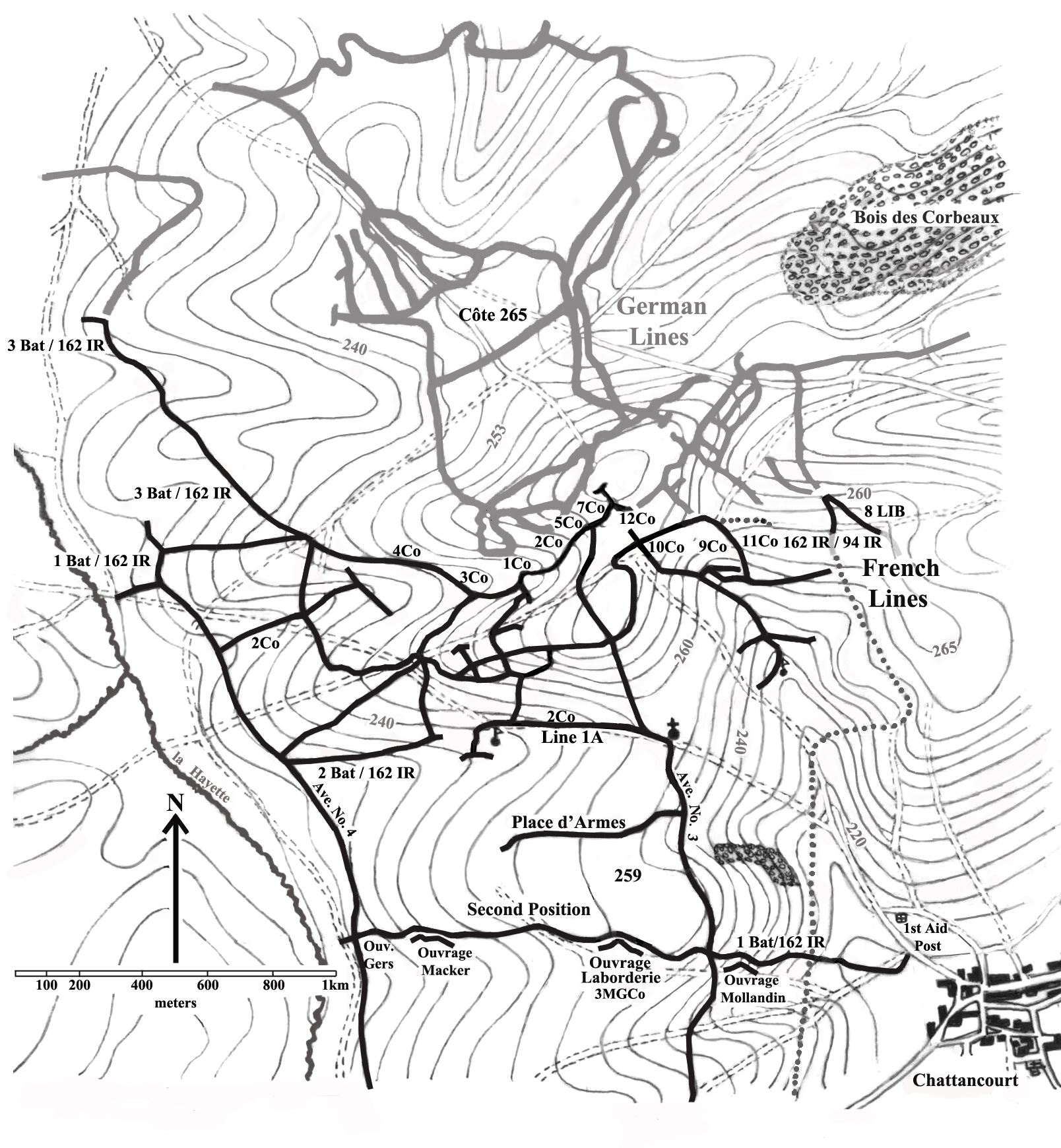

Left: map of Mort Homme showing the disposition of the 42e DI on the evening of 9 April 1916 (drawn by John Bracken). Right: the disposition of the 151 on the evening of 9 April 1916 (source: 42e DI archives).

The situation at the end of the day is as follows: on the left the front of 1 Bat. has held; 5 and 7 Cos. are back in their former trenches; 12 Co. is in the Boyau de Chattancourt; the remnants of 10 and 11 Cos. are along the Cumières Road. An unknown gap exists between the right of the 151 and the 8 BCP. A reconnaissance by an officer to find the 8 BCP determines that the chasseur battalion is located on the north crop of Chattancourt, having three companies in line and one in support. There is a gap between the two units of around 600 meters. Lieut.-Colonel Moisson instructs for half of 9 Co. (the only element of the regiment still held in reserve) to move to the left of 11 Co. (now reduced to only eight men).

Meanwhile, during the night the first elements of 83 Brigade began to arrive as desperately needed reinforcements. A company of the 94 RI was sent up as reinforcement to the left of the 8 BCP to help close that hole. Later that night, a company of the 162 RI would be rushed up the hill to join the company from the 94e and thus form a modest patchwork defense. Even with the meager reinforcements, there still remained 150 meters of ground with no significant force to guard it. The distance was only covered by a scattered line of men placed in shell holes. Measures were also taken to improve the defensive works. It fell to the Territorial Engineers Company 6/3 to complete an important itinerary of work on Mort Homme. The engineers worked hard throughout the night in digging a trench to connect the positions of 7 and 10 Companies and a second one a remarkable 150 meters in length to reconnect those of the 10 and 11 Companies.

Sous-Lieuts. Camusat de Riancey (KIA 9 April 1916) and Mesté.

As would be expected, casualty reports were sketchy at best. Losses for the regiment on 9 April compiled in regimental reports and the JMO differ. One report had the losses tentatively at 29 killed, 158 wounded, and 316 missing. The JMO recorded 51 killed (incl. Sous-Lts. Mattei, Guilbaud, Maurel), 149 wounded (incl. Sous-Lts. Poussière, Depoilly, Bertrand, Langlois d’Estaintot, Noël, Erkens, Buisson, Mesté, and Camusat de Riancey whose wounds will be mortal), and 229 missing (incl. Sous-Lieuts. Cavallier, Chazot, (Frédéric) Couplet, Blondet, and Loubere all of whom were presumed dead). The divisional record has the total number closer to 500, and when compared to regimental rolls, this number would seem closer to the mark, though still dubiously low given what is known of the losses suffered at company level. The 2 Battalion was practically wiped out. The 3 Battalion had also suffered heavy casualties, especially among 11 and 12 Companies, which had each been reduced to just a squad. Only 1 Battalion was still intact. As is the custom when considering the losses of missing in Great War combat, it can be assumed with a degree of certainty that most of these were in fact dead. There are few reports of French prisoners being taken and given the nature of the combat at Mort Homme, that is not surprising. The fate of most of the missing was likely that of a horrific demise – blown to atoms or pulverized by the shells, or buried underneath the geysers of earth thrown up by them, or simply struck down and unaccounted for in one of the thousands of craters that punctuated the landscape.