Trench Journalism in the French Army

Beginning as early as the fall of 1914, French soldiers began producing newspapers (journal de tranchée), written by soldiers, for soldiers. The study of French trench journalism from 1914-1918 is a study of the very mentalité of the ordinary French soldier -- le poilu -- of the Great War. Trench papers are windows into the daily lives of those who fought, suffered and died under the most horrendous of circumstances. Seeded in the Republicanism of the French national sentiment, trench journalism was driven into existence by a brutal war that dramatically alienated those on the "front" from those in the "rear." The gaps between reality and fiction, practicality and uselessness, belonging and isolation -- all facilitated in the creation of this unique, home-spun outlet of individual expression. In a war where the rights of the individual were nearly non-existent, where love and purity, empathy and reason were violently torn apart, trench papers served to inform, connect, and entertain the ranks. They helped to restore some small bit of dignity, humanity and control to those who felt powerless against a war that pitted man against matérial. Trench papers were the view from the bottom up -- the view of the pauvres purotins ("bottom feeders").

Most of the trench papers were directed, edited, written and illustrated by front-line soldiers. The readers were the common fantassins, ("foot soldiers"), mostly farmers and laborers before the war. The editorial teams meanwhile tended to be from a middle-class and urban origin, and were almost entirely made up of NCOs and junior line officers. They shared the same hardships and miseries as the readership, and were therefore able to draw directly on their personal experiences for material. The creation of trench papers was partly in reaction to the periodicals of the civilian press and the the official military communiqués. Soldiers knew both to be filled with what they referred to as 'bourrage de crâne' (literally, "head barrage," or "eyewash"). There was a commonly held sentiment among soldiers that that "their" war, the real war, was presented inaccurately in the national press and by the top military brass. While trench papers produced by the combatants themselves did exist in the armies of the Central Powers, they were much more common in the Allied armies. And amongst the Allied armies, the French by far lead the way in the sheer number of titles. Trench papers were made by troops operating on all fronts, by prisoners of war, convalescents, engineers, airmen, sailors, the artillery and the infantry. Distribution varied greatly, from those made specifically for a handful of men to others produced for an entire division. Some titles were produced in the front lines, while others were edited in much less dangerous conditions, either by rear-line units or by active units billeted in the rear on rest.

In fact the question of "authenticity" - whether a paper was written by a true front-line unit or not -- greatly preoccupied the editorials. A large portion of column space was devoted to justifying an editorial team's front-line status, and disparaging colleagues they considered too sheltered. The source of this sensitivity derived from the scorn felt by those troops serving at the "true" front toward those who were considered to be rear-line troops. But just as there were different degrees of "the front," so too were there degrees of being in "the rear." For all sakes and purposes, the military operational zone (or "zone of the armies") consisted of four, often indistinct areas: the rear of the rear, the front of the rear, the rear of the front, and the front of the front. Those men serving at the front of the front invariably looked down on any individual serving in the other areas, including those who might be regularly exposed to danger but who were considered to be in the rear of the front. Moreover, even the status of a unit was subject to great change due to the unpredictable nature of the war. For instance, a paper produced by a group of territorials who normally are kept in reserve might be made into an "active" line unit. Suddenly, their paper has become one of exposed fighting troops.

The tone, format and contents of a given trench paper might vary considerably over a period of months as different teams came and went. With frightening regularity, entire editorial staffs were decimated in combat, sometimes resulting in publication ceasing altogether. Likewise, the frequency of circulation was also subject to great change. Some were put out regularly every week or every month while others were done whenever time and circumstances allowed. Great attention paid to literary and aesthetic detail led editorial teams to constantly improve their papers, including printing methods and reproduction of drawings and paintings. Some even made attempts at using color, though the results were generally disappointing.

The most common stated purpose of a trench paper was to inform the troops of goings-on in the absence and mistrust of the regular civilian newspapers and military communiqués. Additionally, they were meant to sustain morale through simple entertainment or diversions. It was in their angry rejection of the civilian press that soldiers began creating their own. The trench press also took on the task of strengthening the ties of solidarity between the men and occasionally made attempts of instilling discipline. The content featured in the average paper could include: briefings on the unit's latest operations and movements; articles, limericks and poems dedicated to pieces of the soldier's equipment, uniform, or the rations he received; cartoons and illustrations; word and number games, and crossword puzzles; diatribes on daily life in the trenches, the boredom, the fear, the repetition; reflections on being in combat, on the pain of losing friends, on the reasons for fighting and the motivations for continuing to fight.

Often though the stated objectives of the editorial teams concealed less public motives. Censorship, along with the atmosphere of la union sacrée -- the newly formed sense of French nationalism -- played central roles in shaping trench journalism from the start. Many of the more patriotic, chauvinistic, and triumphalist themes that are presented in the columns can be explained by the constraints put into effect by those monitoring them. In order to achieve publication, a thoroughly conventional format had to first be presented. Subsequently having proved their merit, they could then relax this rigid facade to a degree. The pressure of censorship, however, varied widely due to a lack of clarity in the directives of the French High Command, as there was an absence of any official guidelines. Censoring was done by officers of the company and regiment who were often sympathetic to their men's plight. Thus, efforts in general proved relatively ineffective and tolerant. Censorship generally limited itself to information of a logistical or geographical nature, political references, and excessively sharp or graphic suggestions and descriptions. Stricter control would follow only in the aftermath of the mutinies of 1917, when Pétain ordered tougher regulation of content.

Surviving copies of trench papers are rare, with less than two hundred in existence today. The degree of conservation has varied accordingly to two main factors: their date of issue and their method of production. The earliest papers (late 1914 or early 1915) are less likely to have survived compared to those of the later periods (late 1915 to 1918). Furthermore, the simpler the production process and the smaller the circulation, the lower the survival rate. Papers sent to the rear for printing in large numbers have survived longer than the modest handwritten sheets with a distribution of only a few dozen copies. Because the early-war papers were mostly made in this hand-made format, they survived in lesser numbers. It is fair to assume, though, that handwritten papers were more numerous in the trenches, as production difficulties (including costs) would have deterred the more sophisticated methods to the soldiers. Oftentimes, the trench paper was simply a single handwritten copy passed from man to man. Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau estimates the total number of separate front line titles published between 1914 and 1918 in the French army at approximately four hundred.

Hidden just under the surface of the papers' pages there is a definite current of escapism, a driving desire to get away from the monotony, the cafard ("depression"), the hardships and death. Trench papers served as an outlet for the soldiers' anger-at those in command and at the war in general. In the long-term, they acted as chronicles, preserving the memories of the combatants from oblivion. Through the use of news reports, poetry, artwork, humor, and the recounting of anecdotes from ordinary soldiers, trench journals acted as a mouthpiece for the voiceless. They continue to remain a confusing mix of insincere bravado and moving personal testimony. Sometimes elusive, always disturbing, this crucial form of self-expression served to raise the poilus up from the anonymity threatening to swallow them.

A Sample of Trench Journal Titles:

"L'Ambulance" (The Ambulance)

"L'Anti-Cafard" (The Anti-Depressant, lit. The Anti-Roach)

"L'Antiseptic" (The Antiseptic)

"L'Argonnaute" (The Argonaut)

"Artilleur Déchaîné" (Raging Artillerist)

"L'Autobus" (The Meat, lit. The Bus)

"Le Barbelé" (The Wire)

"Le 3e Battalion" (The 3rd Battalion)

"Le Bâton-Pilote" (The Pilot-Stick)

"Bellica" (Bellica)

"Le Boche-Scout" (The Boche-Scout)

"Bombardia" (Bombardia)

"Bombes et Pétards" (Bombs and Grenades)

"Boum! Voilà!" (Boom! There you go!)

"Les Boyaux de 95e" (The 95th's Communication Trenches)

"Bulletin des Écrivains" (Writers' Bulletin)

"Le Cafard Muselé" (The Muzzled Depression, lit. The Muzzled Roach)

"Le Camouflet" (The Affront)

"Le Canard du Biffin" (The Foot-Soldier's Duck)

"Le Canard Poilu" (The Poilu Duck)

"Le Chasseur à Pied" (The Foot-Chasseur)

"Le Cladron Républican" (The Republican Cladron)

"Le Cochon est Mort" (The Pig Is Dead)

"Le Coin-Coin" (The Comfy Spot)

"Le Coq Catalon" (The Catalonian Cock)

"A Corsica" (In Corsica)

"L'Echo des Dunes" (The Dunes News)

"La Côte 160" (Hill 60)

"Le Courrier des Sapes" (The Saps Courrier)

"Le Cran Éclat" (The Gut Fragment)

"Le Crapouillot" (The Mortar, lit. The Toady)

"Le Cri de Poilu" (The Poilu Cry)

"Le Crocodile" (The Crocodile)

"Le Diable au Cor" (The Devil with the Horn)

"L'Echo des Bombes" (The Bombs News)

"L'Echo des Cagna" (The Bunker News

"L'Echo du Group Cyclist" (The Cyclist Group News)

"L'Echo du 13e Territorial" (The 13th Territorial News)

"Face aux Boches" (Across from the Boches)

"Fourbi et Gourbi" (Shack and Bunker)

"Gazette d'Alsace" (Alsace Gazette)

"Gazette du 155e" (155th's Gazette)

"Le Jus" (Coffee, lit. Juice)

"Le Khaki" (Khaki)

"Lapin à Plumes" (Rabbit with Quills)

"Mar-Gaz" (Mar-Gas)

"La Marmite" (The Stewpot, i.e. the artillery shell)

"Le Mitraille" (Gunfire)

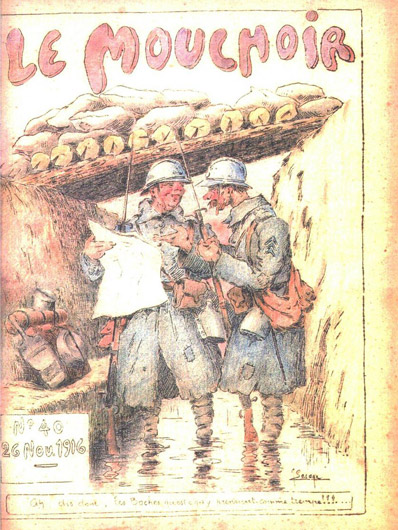

"Le Mouchoir" (The Handkerchief)

"La Musette" (The Haversack)

"Notre [R]ire" (Our Laughter/Anger)

"On Les Aura" (We'll Get Them)

"Le Paix-Père" (Father-Peace)

"Le Périscope" (The Periscope)

"Le Petit Embusqué" (The Little Shirker)

"Le Poilu du 37e" (The Poilu of the 37th)

"Le Poilu Grognard" (The Grumbler Poilu)

"Le Poilu Humoristique" (The Humoristic Poilu)

"Le Pou" (The Louse)

"Le Rat à Poil" (The Hairy Rat)

"La Revue Bisquitée" (The Buscuited Review)

"Sac à Terrre" (Sandbag)

"Sans Tobac" (Tobaccoless)

"Sous les Marmites" (Under the Stewpots, i.e. artillery shells)

"Tac à Tac Teuf-Teuf" (Rat-a-Tat-Tat)

"Le Trait d'Union" (Hyphenated)

"Tranchman-Écho" (Trenchman-News)

"Transporteur" (Transporter)

"Tricolore" (Tricolor)

"Le Troglodyte" (The Troglodyte)

"Le Ventre à Chou" (The Cabbage Belly)

"Le Verre Solitaire" (The Lonely Drink)

"Le Zou-Zou" (The Zou-Zou)

"Le 120e Court" (The 120 Short)