Helmets

This page covers to two forms of head protection issued to the French army during the Great War, with a focus on the line infantry. The first was a mediocre temporary measure provided to the infantry, the brain-pan. The second was the famous Adrian helmet, which would remain in production until after the Second World War and was adopted as the standard helmet by a multiple foreign nations.

Note: All images used without permission. Original sources are cited at bottom of page.

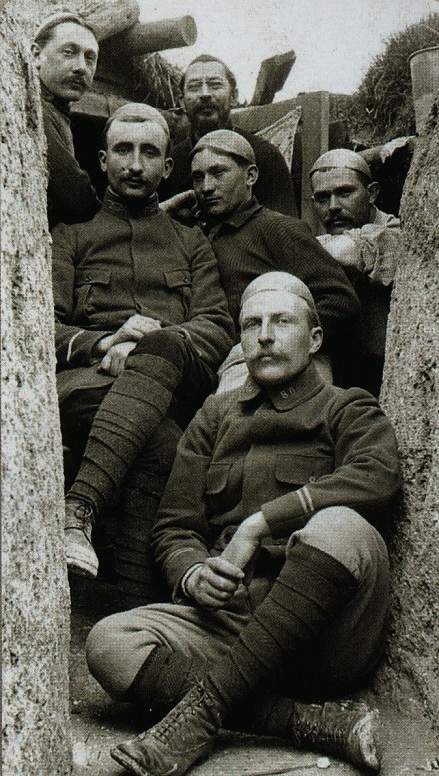

As the French army’s casualties rapidly mounted in the summer and fall of 1914, it became evident that head wounds would be a defining injury of the conflict. Most often these had been inflicted by shrapnel, shell fragments or other flying debris. To help reduce the number of head wounds, Quartermaster General Louis Adrian proposed in December 1914 the production of protective headgear. The first initiative was rudimentary in the extreme: a steel bowl called the cervelière ("skull-cap, or more literally, “brain-pan”). The idea originated with reports of the soldiers’ mess-tins being struck by shrapnel balls but had not been punctured. At first, the Grand Quartier Général (G.Q.G.) remained reticent about the brain-pan. The belief was that the war would be over before the helmets could be produced and distributed to the troops. Yet after further convincing from General Adrian, G.Q.G. signed-off on production of the economized form of head protection.

.jpg?dl=0) The brain-pan was a stamped steel skull-cap intended to be worn under the kepi. In actual use, the troops took to wearing them on top for comfort. Manufactured in three sizes (small, medium, large), it was .5 mm thick, semi-spherical in shape, and had two holes drilled into either side allowing it to be hung by a cord while not in use. French troops also found another use for the brain-pans. They made for good cooking receptacles or even, when in need, as chamber pots. Between December 1914 and February 1915, 700,000 brain-pans were made, with 200,000 actually being issued to the ranks. Yet they offered only mediocre protection against small shell fragments, shrapnel and stones. Something far better was needed.

The brain-pan was a stamped steel skull-cap intended to be worn under the kepi. In actual use, the troops took to wearing them on top for comfort. Manufactured in three sizes (small, medium, large), it was .5 mm thick, semi-spherical in shape, and had two holes drilled into either side allowing it to be hung by a cord while not in use. French troops also found another use for the brain-pans. They made for good cooking receptacles or even, when in need, as chamber pots. Between December 1914 and February 1915, 700,000 brain-pans were made, with 200,000 actually being issued to the ranks. Yet they offered only mediocre protection against small shell fragments, shrapnel and stones. Something far better was needed.

le Casque Adrian (“Adrian helmet”)

Though the brain-pan produced only marginally positive results, its use still led to a decrease in the number of casualties. This caught General Joffre’s attention, and by the end of February 1915 he was convinced of the need for head protection. He ordered that a more suitable helmet be produced and Adrian jumped to work. His idea was to create a helmet that both offered both increased protection and comfort. It had to weigh as little as possible yet be strong and easy to manufacture in large quantities. His design was largely based off preexisting helmets employed by the light-cavalry, which in turn had been inspired by the Bourgoignotte helmet of the medieval times. In March and April 1915, manufacturers were given the prototype of the infantry helmet. These producers had previously been making the more complicated and ornate pre-war helmet for light-cavalry, as well as those employed by the Paris fire brigade. Adrian submitted his design to the French authorities for final approval at the end of April 1915, with production beginning immediately.

The helmet was .7 mm thick and weighed roughly 1.8 pounds. It was composed of four pieces: a shell, a visor, a neck guard and a crest. The visor was 50 mm wide (inclined at a 22 degree angle), the neck guard 44 mm (inclined at 45 degrees). Along the top edge of the crest were two ventilation slits. On the crown, a badge was attached in the form of a flaming grenade and embossed with the letters “RF” (République Française). The assembly of the helmet was done via stapling and soldering. Soon after production began, it was evident that the joint of the neck guard and visor would need to be reinforced. Originally the two were simply soldered together. As such, two rivets were added, either one below the other or placed obliquely to one another. (An exception appears to be with the manufacturer Japy, which continued to retain a soldered-only joint throughout the war.) The color used in painting the helmet was a light grey-blue, which was sprayed on. Once fired in the kiln, the paint darkened to a bright, luminous blue varying in shade.

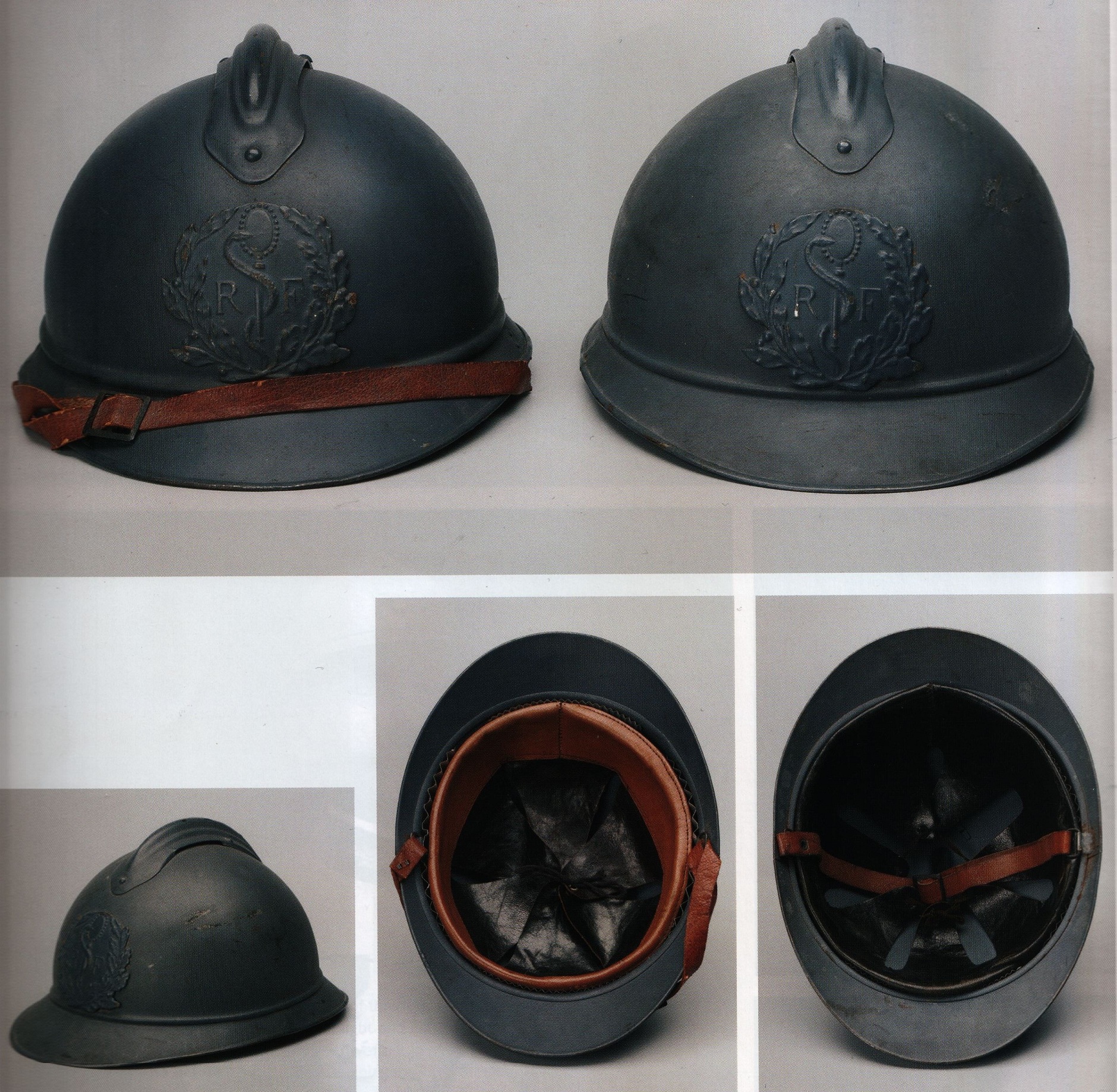

The helmet liners were originally made of sheepskin but would later be changed to the more resilient goatskin. The first model liner was cut from one piece (sheepskin) and consisted of seven teeth with a copper eyelet at the end of each to take the drawstring. The leather was blackened and varnished. Beginning in the fall of 1915, a second model would be used consisting of two pieces sewn together, the leather being left natural. The liner was sewn to a strip of recycled wool (madder red or dark-blue), which was itself mounted onto four strips of corrugated aluminum. The metal strips secured to the shell of the helmet via hooks soldered to the shell. The chinstrap was similarly made of first sheepskin (blackened) and then, after August 1915, goatskin (natural brown). Two mm in thickness, it was tightened using a black-lacquered iron buckle and secured to the helmet by a brass rivet (non-regulation copper rivets were also seen).

The helmet was manufactured in three sizes A, B and C, each being subdivided into three inner lining sizes. The result was nine sizes of head circumference, from 54-62 cm.

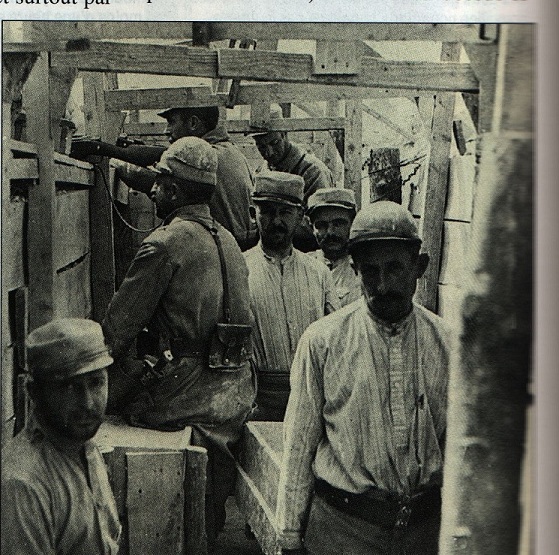

Of the roughly fifty manufactures initially called upon to put out the helmet, only fifteen are retained: two to produce the steel sheet metal, five to produce the head pieces and chinstraps, eight to manufacture and incorporate the paint and position the head piece and chinstrap. The stamping equipment was particularly delicate and complex. It required some fifty tools to create the exploding bomb insignia attached to the crown. It took a good month for production to become regular and to conform to the standards that Adrian originally set. For example, the Japy facility was contracted to have produced 529,000 helmets by 1 August 1915 but had only made 141,000 by that time. Yet Adrian remained optimistic as manufacturers steadily increased production levels. At the end of August, 52,000 helmets were being turned out daily. By the start of the Champagne offensive on 25 September 1915, 1,600,000 Adrian helmets had been distributed to the army. By the end of the year, this number was over 3 million.

The price of manufacturing each was only 3.35 francs. In comparison, a regulation kepi cost 3.80 francs each. And when compared to the price that British manufacturers were asking for each of their helmets–15.65 to 18.75 francs–this was a real bargain. Meanwhile, French industrialists, steel manufacturers and those who had declined to participate in the production of quartermaster helmets, fashioned for their personal profit a model close to the official Adrian. Primarily purchased by officers, these commercial helmets were sold at a price of 20 to 25 francs and were of a much inferior quality, aside from a fancier liner. The metal used in its construction proved too rigid and when struck by a projectile tended to fracture into splinters, only adding to the trauma of the wound. At the end of September, Joffre prohibited the production and use of these commercial helmets in the zone of armies.

The appearance of the Adrian as standard equipment of the soldier showed an immediate decrease in the number and severity of head wounds. The helmets, at first designated to just the infantry, are soon distributed to all the branches of service. The only distinguishing characteristic on the helmet between each of the branches was in the badge mounted on the crown. For the infantry and cavalry, it was the flaming grenade; for light-infantry (i.e., chasseurs), a horn; foreign marksmen (i.e., African tirailleurs and zouaves of the French Africa Army, a crescent moon; artillery, two crossed canons surmounted by a flaming grenade; colonial troops, an anchor surmounted by a flaming grenade. For the non-fighting wings, the badge was, for the engineers, a cuirass and helmet; for medical, a caduceus entwined by a serpent surrounded by oak and laurel branches; for quartermaster, a fascine with a backdrop of flags and laurel wreaths. Officers sometimes had specialized badges made, which typically incorporated rank insignia. The chinstrap was often replaced with one of higher-quality make, such as braided leather.

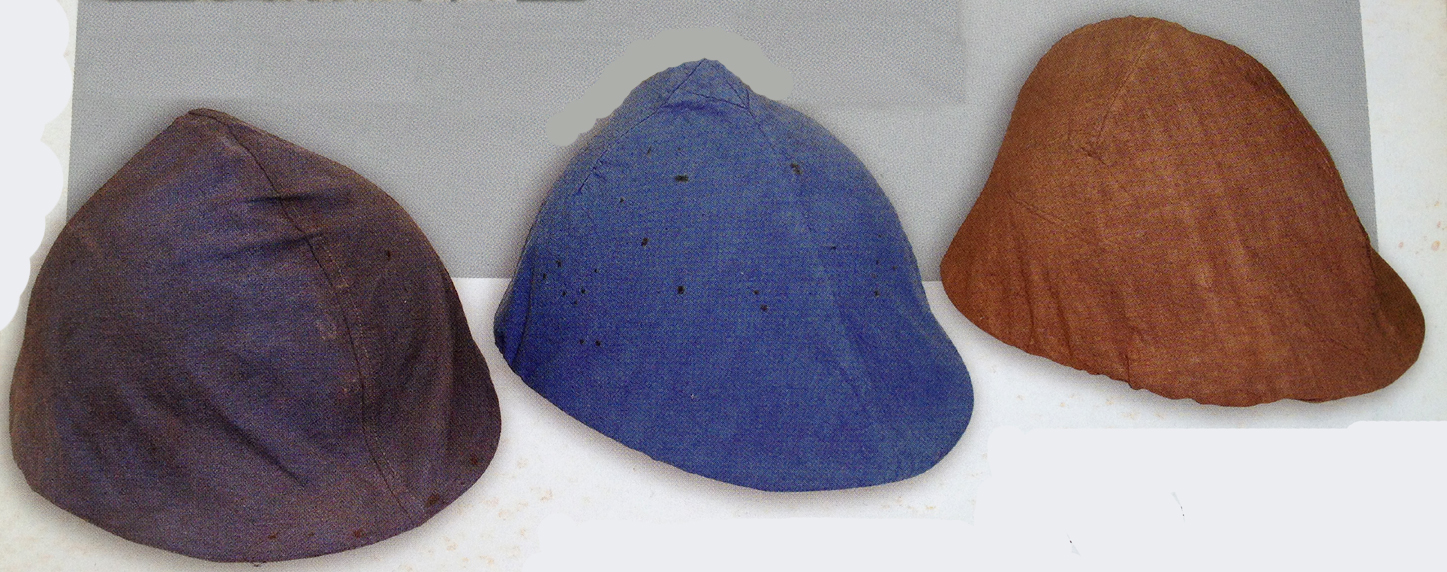

The only serious flaw with the design process was discovered in the field and it came down to paint. Specifically, the glossy finish reflected sunlight too easily, making for an easily identified target even at long distances. As a short-term measure, helmet covers were distributed beginning in November 1915. In practice, helmet covers were already being made locally without waiting for the official order to be issued. They were made of various types of canvas, including the same material as used in French tent-canvases. The order decreed that the covers were to be made in the same iron blue-gray (cretonne) cotton used for the early war kepi covers. In reality, khaki and beige was used more extensively. Generally the construction consisted of two pieces sewn together along a central seam and equipped with a drawstring. Commonly, in the absence of a helmet cover soldiers camouflaged their helmet with mud. An unintended side-effect of the helmet covers, along with the self-application of mud for camouflage was an increased rate of infection in head-wounds, as cloth and mud particles were blasted into the wound. On 15 October 1916, both helmet covers and the improvised practice of camouflaging the helmet with mud were officially prohibited. Despite the ban, helmet covers do appear in use here and there until the end of the war. Ultimately, the helmet cover was yet another ephemeral item that defines the look of the poilu in 1916.

In June 1916, more permanent efforts were made to reduce the visibility of the helmets by reducing the glossiness of the paint. It was found that if the helmet was fired for an extra period of time in the kilns, the result was a darker tint that had a matte grey-blue appearance. On 8 July, distribution of these less visible helmets began. Helmets distributed before the new painting process began were either reclaimed and repainted, or were painted over at the local echelon using a matte dark-gray or dark-blue. In the latter case, the paint was applied using a brush.

Meanwhile, distribution had soared to 7 million by the end of 1916. That year, France began selling the Adrian to foreign armies at the price of 6 francs each. Italy bought 1,600,000; Russia, 340,000; Belgium, 208,000; Serbia, 123,000; Romania, 90,000; Holland, 10,000. By war’s end, a total of over 20 million Adrians had been made. On 18 December 1918, a decree is made awarding a helmet to each officer or soldier having belonged to an army formation. This helmet is provided with a plaque, a brass souvenir covering over the visor and bearing the inscription “Soldat de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918” (“Soldier of the Great War 1914-1918”). These ceremonial helmets are sent out on the 16 April 1916. The Adrian remained the standard military issue in the French army until after World War II, and was also used by the French police up to the 1970s.

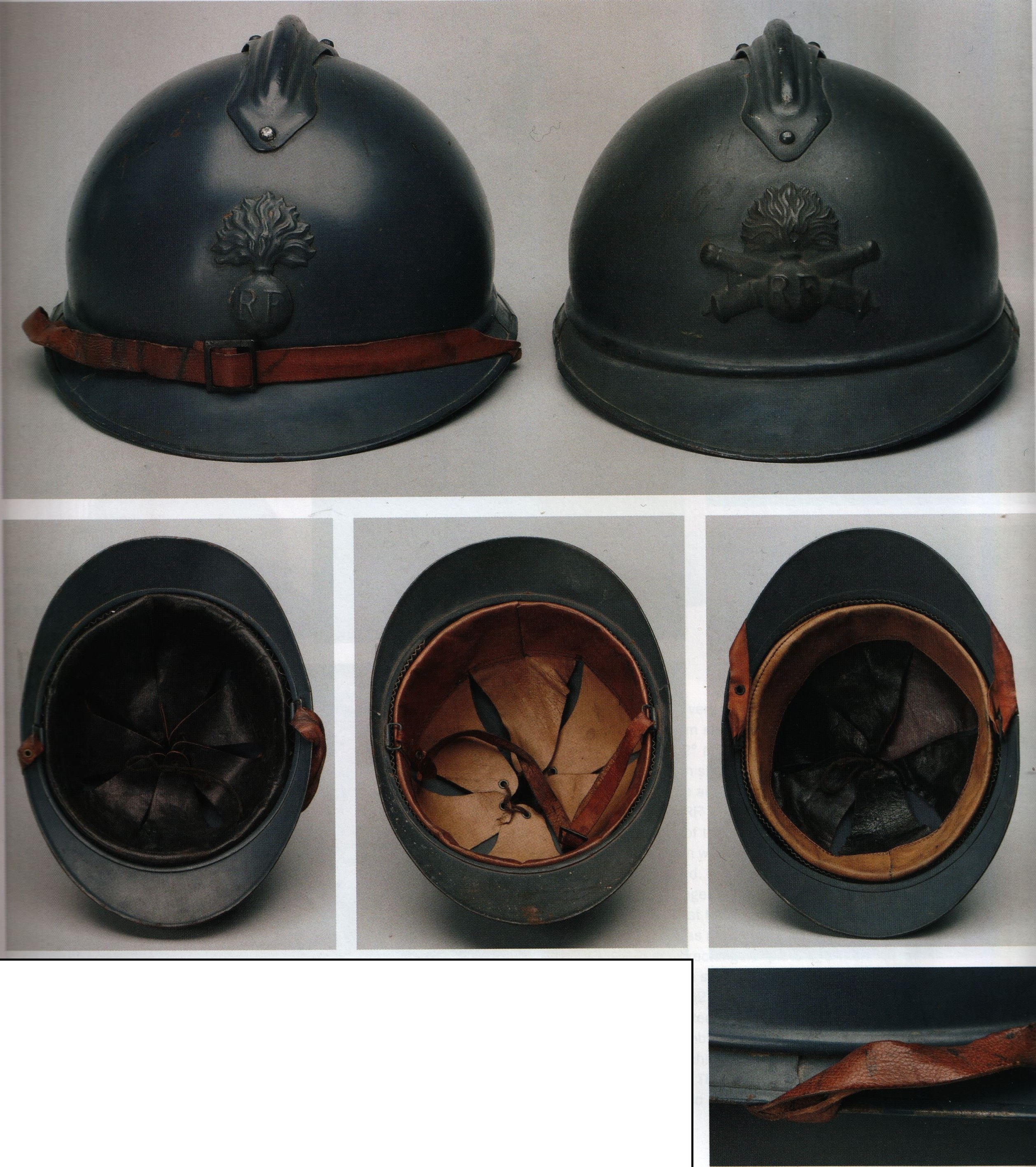

Example of the 1st model Adrian showing the light, luminous quality of the early paint.

Another example of the 1st model Adrian showing the luminous quality of the early paint, although here quite dark in tone. It bears the hunting horn badge for chasseurs. The early model liner is also shown.

Example of the 2nd model Adrian in mint condition, showing the darker, more matte quality of the later paint. It bears the crossed canons badge for artillery. Details of the helmet are also shown including the early model liner metal spacers, rectangular chinstrap receiver and headband.

On top row, a comparison of a 1st model Adrian with the early paint (left) and the 2nd model Adrian with the later paint (right). On bottom row, an early model liner (left) and two later model liners. All of these helmets were manufactured by Japy yet minor differences in assembly between each can be seen. The soldered joint of the visor and neck guard is also shown, an assembly feature that Japy continued for the entire war despite later regulations stating the joint should be reinforced with rivets.

Example of a French Africa Army Adrian with crescent moon badge worn by zouaves and Indigenous African tirailleurs.

Diagram illustrating the style differences between manufacturers.

Comparison of variances in the design of the rear end of the crest and the exploding bomb badge for infantry.

Two examples of the joint of the visor and neck guard. This followed an official decision that the joint should be reinforced with rivets starting on the 2nd model Adrian. In the bottom example, the visor overlaps the neck guard, where the opposite is true on the top example.

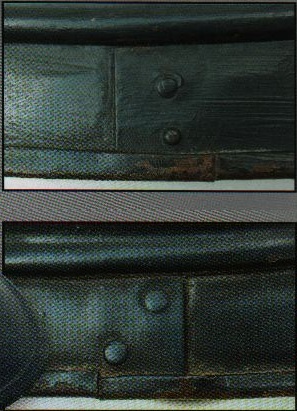

Two examples of 2nd model Adrians, both with later paint type but varying noticeably in tone. The helmets bear the ornate, Cadeceus badge of the medical corps. The helmet on the right was made by the Reflex company and the badge, appearing in a different color, was painted in the workshop, then delivered separately and assembled in the unit. The example on the left features a helmet and badge of the same color, indicating it was assembled and painted in the factory. The example on left has a later model liner, the one on the right, a early model liner.

On top, comparison of early model (left) and later model (right) liners. On bottom, example of an early model liner showing the headband made of recycled madder red wool (left), and the cold-weather model liner adopted at the end of 1915 and made of recycled light blue and iron-blue wool (right).

On top, a 2nd model Adrian in near mint condition. On bottom, a 2nd model Adrian for an officer with fancy braided leather chinstrap. This would have been a private purchase item, a common modification found on officers' helmets. Both helmets bear the bomb and anchor badge for colonial infantry. However, the example on top features a badge and helmet assembled and painted in the factory, while the example on the bottom has a badge in slightly different color, and thus assembled in the unit.

On top, an chasseur officer's helmet with a dark blue paint, hand-painted at the depot. Adorned with the brass rank bar of a 2nd lieutenant welded on, a less common modification also improvised locally. On bottom, a rather light-toned 2nd model Adrian. The paint shown on this colonial helmet seems less common than the typical later paint quality.

Example of a commercially manufacture (private purchase) officer's Adrian. The differentiation in design from the regulation model can be seen, including a badge that does not bear the letters "RF." Although banned after September 1915 because the tempered steel had a habit of shattering when hit, commercial manufactured Adrians remained popular with officers.

Two more examples of private purchase Adrians, both made of tempered steel. On left, an artillery officer's helmet bearing the pre-war, full dress badge (the insignia adopted in Feb. 1915 was not known to manufacturers producing a non-regulation helmet). The helmet is painted dark blue. On right, an engineer officer's helmet also bears the pre-war, full dress design badge. It is painted a bright, light blue. Both helmets feature a chinstrap modeled after the M1884 kepi chinstrap.

Three helmet covers in iron blue-gray, a medium blue, and a beige. The covers were later banned as head-wounds became infected when the cloth was ejected into the wound.

On the left, a helmet cover in light khaki. On the right, a cover in a coarser canvas.

A helmet cover made of the same cretonne cotton in iron blue-gray used for the early war kepi covers, showing how faded this particularly color could become after exposure.

Photo showing an improvised camouflage helmet cover made of a sandbag. This was a common modification made in the trenches.

An example of camouflaged helmet, hand-painted at the depot. Only artillery observers were permitted to war Adrians modified in this fashion. Painted camouflage helmets were exceedingly rare in the French army, unlike in the German army.