First Hand Accounts of the 151e R.I.

Under Construction...11th Lieutenant Raymond Jubert

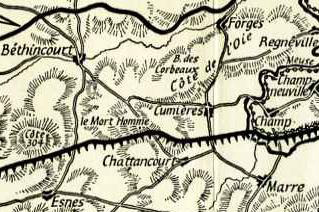

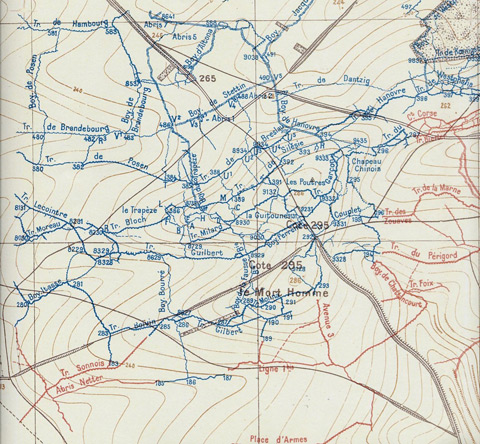

The Left bank positions at Verdun, showing Hill 304 and le Mort-Homme to the west [left] of the winding Meuse River on the far right of the map.

The regiment was sent over to Mort-Homme (Left Bank), on April 6. Jubert's company was held in a reserve position at the base of the hill. On April 8, the 11th Company was put on alert; it would be moving forward soon. Jubert remarked to a fellow officer, "This will do us good. We were starting to get out of the habit of dying."

As he woke up early the following morning, he gazed at the men: "They were sleeping, with no suspicion that death was nearby; like condemned men, they would be awoken only so that they had to die no more."

At 0700 hrs, the German artillery opened up with a massive bombardment on Mort-Homme and the neighboring Hill 304. In fact, it was the heaviest one since the opening of the battle on February 21, and many witnesses described Mort-Homme as resembling an erupting volcano. Jubert watched in awe at the sheer violence of the assault and noted poetically:

"Brushstroke was being added to brushstroke in quick succession, dozens at a time. So heavy that they could suffocate you if you were close, from a distance they looked fresh, harmonious to the eye. Thunderclouds floated across the sky, touched with the color of the morning. The sun has this virtue: beneath it's rays, death takes on pure beauty"

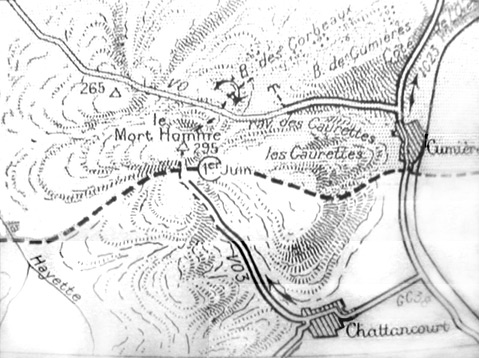

Le Mort-Homme. The 151st was placed on the summit of 295, with Laporte's machine-gun company on the regiment's right flank on the eastern slopes.

Le Mort-Homme. The 151st was placed on the summit of 295, with Laporte's machine-gun company on the regiment's right flank on the eastern slopes. Map of Mort-Homme showing the trench networks, sometime from June 1916 to August of 1917. The French lines are in red and the German lines in blue. This map represents the greatest point of the German advance, having already seized many French trenches on the summit.

Map of Mort-Homme showing the trench networks, sometime from June 1916 to August of 1917. The French lines are in red and the German lines in blue. This map represents the greatest point of the German advance, having already seized many French trenches on the summit.At 1300 hrs the German guns fell silent. Believing the enemy attack to be thwarted, Jubert's company vented itself in hysterical relief -- they had been spared from the attack. Lunch was served to the men who feasted voraciously. As the sun came out, the men sat down to play cards and wait for further orders. Jubert himself was in fact doing quite well for himself with a lucky run when a message arrived from Regiment: the crest of Mort-Homme had been overrun and his company was to retake it immediately. The prospects seemed dire indeed. They would be counter-attacking across open ground since navigating the communication trenches up the slope would only slow their momentum.

Nontheless, there was no hesitation in the men who received the news calmly. As soon as the order had been issued by the sergeant, the men went about silently collecting their gear and filling up with extra rations and ammo. They soon formed up into straight skirmishing lines and advanced up the slopes. Occasionally shouts of encouragement were exchanged:

"We'll show them what men from the North are made of!"

"And men from the Ardennes too!"

"And Paris!"

The majority of the men's faces were grave, though some managed a pale, taught smile when Jubert caught their eye. As he reached the first series of ridges, he looked into the ravine below which was so saturated by artillery fire that it seemed an impenetrable barrier. Yet despite appearances, he manged to find pockets of safety in amongst the deafening explosions and rain of earth and steel. At one point, a shell exploded behind Jubert and hurled a man several meters into the air. As the body plummeted back, it was jerked back up by the blast of a second shell.

As a salvo of shells came tearing down, one platoon quickly flattened themselves to the ground in anticipation. As soon as they exploded, they jumped back up and resumed their place in line. When Jubert and his company arrived at the top of the next ridge, they came upon a lieutenant that had been posted to give last-minute instructions and directions. However, the smoke was so thick that he could offer no assistance. When Jubert inquired as to the location of the Germans, the lieutenant replied: "That's for you to tell us."

The company was split into four platoons: one to advance to the crest through the battered communication trench and the other three to advance across open ground obliquely from the left. Jubert took command of one platoon as they continued on. A wild exhilaration had seized the men now. Some laughed hysterically, while one man shouted: "We're going to beat them! The bastards won't get past us!"

In the wild élan of the moment, another man struck up a popular cafe song and the rest soon joined in. Jubert charged forward, overcome with emotion, dodging machine-gun bullets which beat the ground all around him. He heard the cries of his fellow officers as they were hit but could only think of their fates in a detached sort of way. He was experiencing the out-of-body sensation that often overcame men in combat. The sheer momentum of the charge hurtled them to top of the hill. They leaped over the parapet but found the trench deserted for several hundred meters in either direction. The Germans had made a tactical withdrawal, leaving behind their dead intermixed with the corpses of French zouaves and chasseurs.

In the uneasy calm, anxiety now began to seep into Jubert and his men. To help boost morale, Jubert seized a German envelope lying on the ground and ceremoniously recorded the names of all the survivors to be commendated later. Of the 100 men who had begun the charge, only 10 were left: several sergeants, a corporal and a handful of new recruits from the class of 1916. Jubert made a quick reconnaissance verifying that no other French forces were nearby and that German troops still occupied an adjoining trench, though the latter were unaware of their presence. Jubert decided to hold the ground they had so costly won back.

Jubert jotted down a brief note to Colonel Moisson:

"I don't know where I am, but the position is of the first importance, and I have only ten men to hold it."

He urgently requested that at least two companies be sent up as reinforcement. The first runner carrying the note was wounded almost as soon as he had set off. A sergeant then volunteered who was already bleeding profusely from a chest wound. As Jubert watched him leave, he thought to himself, "There goes another dead man."

As dusk fell, the German bombardment grew in intensity. At 2000 hrs, having received no response from his request for reinforcements, Jubert decided to try to reach the Regimental command post himself. When he finally arrived at the post, he was greeted like a man returning from the grave and was showered with congratulations. Unfortunately, Colonel Moisson had no reinforcements to lend him but promised that as soon as he could he would send a company. Dejected, Jubert headed back up the hill and on the way passed a fellow lieutenant being carried back on a stretcher. The two embraced without speaking, his friend's fate all too obvious to both men. When Jubert arrived back at the summit, he found his men still holding on to their position nervously.

Another 36 hours would pass before any relief came, all the while under non-stop artillery bombardment and machine-gun fire. As he and the handful of dazed survivors that constituted the 11th Company returned to the support lines, Jubert was struck by the sheer ineffectualness of man when faced with such a storm of matériel. Still relying on the metaphor of a painting, he wrote humbly:

"In the middle of combat, one is little more than a wave in a sea . . . a stroke of the brush lost in the painting . . . Courage, in our days, is a currency that is not depreciated, but tarnished by usage."

Jubert won a military medal for his actions and the company received honorable mention in the dispatches. Yet by May, when Jubert was posted back on Mort-Homme, something had changed inside him. Around this time, he began his memoirs which he completed while convalescing after a wound. He recorded this internal-shift in an insightful self-examination:

"What sublime feeling took hold of you as you went into the attack? "

---"I was thinking only of pulling my feet out of the mud they were stuck in."

"What heroic cry did you utter when you had recaptured the crest?"

---"I resurrected Cambronne* because I thought I was done for."

"What feeling of power did you have when you had defeated the enemy?"

---"I was annoyed, because the grub wouldn't get to us and I'd spend several more days without any pinard."

"Was your first act to give thanks to God?"

---"No, I went off alone and relieved myself."

*[Supposedly during the Battle of Waterloo, General Cambronne refused to surrender with a single word: merde! His name, or the phrase "mot de Cambronne," thus served as a polite euphemism.]

Jubert was particularly disturbed by both the ignominy and anonymity of death at Verdun. As he sat on Mort-Homme in May, he gazed up to the sky and enviously watched the vermilion plane of the flying ace Navarre performing victory aerobatics above the French lines after scoring another victory. Triumph or defeat for these men, Jubert reflected "gains equally the cheers of those who die without glory of any sort. They are they only ones in this war who have a life or death dreamt about."

Compared to the miseries of life on the ground for the infantryman huddling in the mud-filled shell-holes of Verdun, under the pounding blows of the artillery, the pilots had a good life. Jubert managed to sum up the foot-soldier's experience somberly when he wrote:

"After twenty months of fighting, where twenty times I should have died, I have not seen war as I had imagined it. No, none of those grand tragic tableaux, with sweeping strokes and vivid colors, where death would be a stroke, but these small painful scenes, in obscure corners, of small compass where one can not possible distinguish if the mud were flesh or the flesh were mud."

Before being killed in Chaume Wood the following year, Jubert reflected on the war itself and the sacrifices he and his comrades hade made thus far. he wrote almost prophetically:

"They won't be able to make us do it again another day; that would be to misconstrue the price of our effort. They will have to resort to those who have not lived out these days. . . ."