First Hand Accounts of the 151e R.I.

Quarter-Master Corporal Henri Laporte

Henri Laporte (class of 1914) was called up as a private in the "15-1" in November 1914. He was wounded twice: first, while fighting in the Argonne in 1915 and second, more seriously on the Somme front in October 1916. After convalescing from this second wounding for the winter and spring of 1917, he was finally discharged out of the army. Laporte saw action in the Argonne, Champagne, Verdun and the Somme.

The following entries are taken directly from Laporte's journals which were compiled into a book, Journal of a Poilu. Translating it is a slow process but check back frequently for updates. New entries will be posted on this page regularly.

I. The Trenches in the Argonne (April-June 1915)II. Battle in the Argonne (June-July 1915)

III. Verdun (Feb.-April 1916)

I. The Trenches in the Argonne (1915)

Tuesday April 20

I'm attached to the 8th Company with one of my comrades (Hannois) from A Group, 1st Platoon, from Quimper*. We picked out our "hut," as it could be called, for it reminded me of a picture from one of the first pages of "The History of France." We get acquainted with our comrades. The ice is quickly broken. "Soup" is had at 4:00 pm, by squads. The vets get together to prepare a fire: a fireplace made with two big stones, replacing the stove. It's our first meal near the front and a great atmosphere. We eat hardily. Afterwards, we use the remainder of the day playing cards. Camping is a lot of fun. With night falling, we unfold our blankets and, after getting set up comfortably under our tents, we fall asleep peacefully. A line of sentinels keeps watch around the camp.

*The Normandy town of Quimper (pronounced, Kam-pehr) was the newly assigned depot of the 151st in lieu of Verdun which, since August 1914, was on the front lines.

Wednesday April 21

The temperature has lowered to a single degree [33º F]. Around 5:00 am, I begin to suffer from some violent colics. Maybe this is typical after eating from the camp kitchens. But they don't last, and after a traditional cup of juice [i.e. coffee], they go away. At 6:00 am, we get the order to depart. We kit-up in a hurry and assembly commences by platoons. At 6:15, my company takes up the march, following 2nd Batallion. We steer toward the village of La Harazée, which is situated in Biesme Valley, roughly a kilometer from the front. After four hours of marching, we pass through Vienne-la-Ville. This village had suffered greatly from bombardment; a little farther is Vienne-le-Château, but we leave this village on our left and oblique on a road bordered by cherry trees, on which flowers could already be seen. At 8:00 am, we enter La Harazée. The moon is still shining, a truly eerie sight; almost all the homes have huge, gaping holes in their rooves; we see no one; the silence is broken by the sound of canon blasts. The column advances as quietly as possible. We are covered in dust and a little tired (pack and rifle weighing down a bit). At 9:00 am we take over our billets (houses, stables partially destroyed). This first exertion close to the lines has wiped us out and as soon as we put our packs on the ground and place our material, we fall asleep on a little straw.

Thursday April 22

Last night was a little disturbed: canon blasts, intermittent fusillade. At 9:00 am, a German plane surveys the village and drops some flares for spotting; the German artillery definitely couldn't see anything, for no shells come to visit us. The day passes with all types of checks and at 7:00 pm we put our packs on our backs to go up to the trenches this time: our last stage as beginners. We enter into the Bois de la Gruerie ["Gruerie Wood"] through a fairly large communication trench. We advance in the greatest silence. Smoking and talking prohibited. We come upon communication trench after communication trench, which are themselves linked to each other. From time to time, the sound of stray bullets passing over our heads. The noise is like a speeding siren, high and shrill. We march now one by one, Indian file. We make some stops, with the intervals between us lessened more and more. It's a sign that we're not far from the first line trenches. We start coming across other foot-soldiers who are departing for rest; the relief has begun. We go up into a deep communication trench covered with logs; no light makes it inside. The logs can no longer be distinguished, and at one point we hear..."Cambronne's word!"*

*Supposedly during the Battle of Waterloo, General Cambronne refused to surrender with a single word: merde! His name, or the phrase "mot de Cambronne," thus served as a polite euphemism.

We finally reach the end of the climb; we're now in the second line trenches, about five meters from the first line. An order comes along in a hushed tone which we pass along: "Fix Bayonets." First moment of excitement. I ask the man next to me, a vet: "Are we going to attack?---"No," he tells me, "but it's a precaution taken when going up into the first lines."

Everything's in order now: all are at their post. We no longer have to keep our ears open, for the Germans are very close by, their trenches are placed seven or eight meters from ours. There's even a 'small post' to my right which touches, or very nearly, a German 'small post.' Our trenches are pretty deep-about two or three meters-they're made up of gabions and sandbags. These [sandbags] protect the look-outs at the loopholes. There's a loophole about every two meters. Rifle shots are exchanged between one side and the other. During the night we can make out clearly the enemy trenches by their flares launched from different points along the front. This first night passes without any major incidents.

Friday April 23

I haven't slept a wink. Day rises and soon the sun begins to shine its rays on the monotone countryside. Actually, we can't imagine what it looked like in former times. Now it's only pieces of jagged trees and dead wood, entangled in masses of barbed-wire; helmets, rusted rifles, scraps of material here and there indicating the places of fighting. Our second day in the trenches comes to a close. We've devoured our food and up until now, we find this life...how to put it?...if not agreeable, at least full of suspense! Around 1:00 am, the 40th Division (Vienne-le-Château sector), to our left, attacks the German lines. The canon thunder without stop, the explosions going off two or three kilometers from us, without interruption. It's truly a great spectacle. If only it were a matter of mere fireworks! Alas, some men fall. The sky is streaked with flares; being in the middle of these fires is a fracas (which is frightening). This is, however, just a taste, a prologue. After an hour of this uproar, everyone calms back down little by little. In our sector, for the moment, nothing stirs. We redouble our watch at the loopholes. Our second night comes to a close. It's just a warm-up.

Saturday April 24

I haven't slept since our arrival, and I have fought off sleep since the sun rose. It's 8:00 am. Our 75s begin to fall on the German trenches. These shells graze over our trenches in an ear-splitting whistle and explode in a roll of thunder on our neighbors across from us. We get the order to evacuate the first line trench which is occupied by our whole platoon. We fill back into the communication trenches of the second line. Just as we do so, the Germans inundate the emplacement we've just left with bombs. The fire of our 75s redoubles in intensity. We've fixed bayonets. On our part, we throw grenades into the German trenches. One of my comrades, standing next to me, is wounded by a bomb fragment. Another has his leg crushed into pulp. A third is terribly slashed open, his blood soaking the bottom of my greatcoat, for we are all crouching down, no longer standing to throw grenades. This demonstration lasts two long hours. I don't have a scratch on me. It was our baptism of fire. My poor comrades are carried out by stretcher-bearers. These are the first I see leave. I begin to realize that this is what war is. But are we not here to defend our soil, which the Germans have treaded upon? We swear at this moment to avenge our comrades. Already one, who had just arrived, has died. He died a brave man.

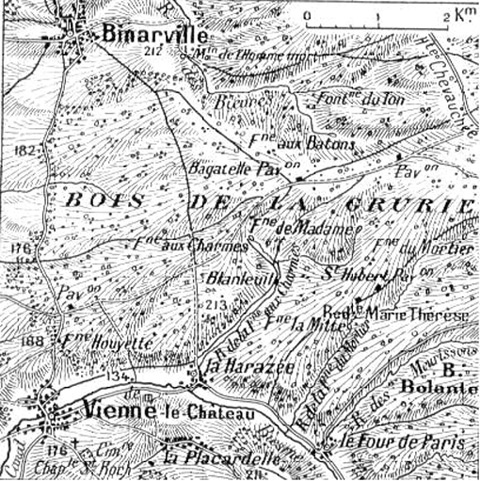

Detail of map showing Blanleuil and portions of the Fontaine-Madame sector that reflects the trench layout closer to as it existed in the spring of 1915.

The tossed and partially destroyed trenches are reoccupied and repaired as quickly as possible. At noon, our platoon is replaced in the first line by a reserve platoon, whose place we take in the second line. We're now a dozen meters from the Germans, at the entrance of a communication trench. I forgot to mention the name of our sector. It's called Blanlil [Blanleuil]. In the second line, we have a bit more comfort: some shelters composed of holes dug into the earth two or three meters deep and covered over with logs. I counted a shelter about every five meters. A squad of ten men was lodged in two shelters, with the exception of the picket line of sentinels, ready to give the alarm. Despite this, we were all on "high-alert." In this second line trench, fire-steps were built in case of attack, placed facing the enemy. Cavities dug into the earth allowed one to sit. The shelters were occupied only during bombardments and during the night in order to take a rest.

As we were getting settled in, I began to smell a bad odor which was coming from the place where I was sitting. After awhile, because of my stirring about, I could no longer stand, nor my comrades, this smell which gradually turned our stomachs more and more. I dislodged with my spade-shovel a little bit of earth, and to our great surprise, I discovered, horrified, that for the past two hours I had used the putrefying corpse of a German soldier as a seat. We went about completely unearthing it. Stretcher-bearers removed it in a tent canvas, after having disinfected the place with chlorine. What a macabre operation! After having reconstructed the fire-step, we settled in once again. Hardly had we finished than we see heading back from the first line a dozen of our comrades (it was 5:00 pm). They informed us that the trench they had occupied was mined and could blow at any moment. It was the first time that we were going to attend such an event.

We were provisioned with grenades, and after having received the necessary orders, we waited impatient to see. A quarter of an hour had hardly elapsed when we felt the earth tremble and, as soon as it did, a frightful din; two or three tons of earth, including dead bodies, were projected high into the air. Shouts, curses, rifle shots. The 75s went into action too. The mine had been blown, tossing up the German trenches. All together we immediately pelted theses trenches with a volley of grenades. We were so overexcited that, throwing aside all precaution, we were standing on the fire-steps, exposing half our bodies to the enemy's shots. The sergeant-major, our platoon leader, yelled for us to get down, but we couldn't hear his shouts. We were enraged, and threw without let up the missiles which sowed death across from us. It was war: to protect yourself you must put your adversary out of the fight. What's more, is that it was reciprocal. After half an hour of this deluge of explosions, only the 75s continued to harass the enemy trenches; we're given the order to cease our grenade barrage. Losses were minimal in our company (two killed and several wounded) but the same could not be said about the other side...All day we've heard muted blows coming from underground galleries being dug under our lines by the Germans. Their goal was to blow up an advanced part of our first line trenches, then to occupy it in order to make the flanks of the excavation untenable and force us to abandon a good part of this advanced point at Blanil. But in their rush our enemy had taken a dynamite and cheddite charge too powerful. Instead of exploding under our feet, the charged turned back on them and blew up the German first line, burying all of its occupants and causing heavy losses in the German ranks. We were still feeling the glow of our first victory when our lieutenant commanding the company (Lieutenant Couplet), if my memory serves me well), accompanied by the 1st Battalion Commander [Lieut-Colonel Moisson], came to congratulate us for our handsome debut. We were now real "poilus"...

In the course of the afternoon, the 6th Company, placed in liaison on our left, send off some big, winged bombs, fired from trench artillery [58 mm mortars]. The strong explosions, which can be heard as they fall, shake the ground and fill the ravine situated behind us with interminable echoes. From their side, the Germans send us "Minemmverferds" [minenwerfers]. These are a type of elongated bomb which are also terribly deadly. (We need to be on our guard, for these missiles were very dangerous. To give you an idea, it's a pipe 20 cm in diameter by 1.2 meters high, charged with melinite and cheddite. It's true that our winged bombs are as equally deadly, if not more so, as discovered by the observations of our dismayed intelligence agents and by German prisoners as well.) This exchange of "prunes" [i.e. bullets] lasts until 8:00 pm. There are losses on both sides. The rest of the night passes by without notable incident.

Sunday April 25

At 6:15 we are relieved by the 5th Company. We go into reserve in the 2nd line, on one of the sides of the Blanlil ravine [between Blanleuil and Ravin Sec]. We take the descending communication trench. We had hardly arrived at the bottom of the hill when we received some big bombs, which fortunately fall to either side of the communication trench. We adopt the "shuttle" system, or in other words rushing this-way-and-that, in order to evade these terrible projectiles. The trench is so narrow that it is difficult to get out of the way of them. Suddenly from the enemy lines we see a "Minemmverferd" [sic] arriving at zenith of its high trajectory. It feels like it's going to come down right on top of us with dizzying speed. Frozen in place by the sensation, incapable of reacting, we wait for certain death: the crampness of the trench and our position, everyone pressed up against each other, nobody can maneuver out of the way. Thankfully luck would have it that the projectile crashed down without going off about two meters from me. What a bloody sigh of relief! It would've been truly absurd to be killed in such conditions as here. Yet how many soldiers had suffered this sad end! The moment of suspense and emotion passed, my comrades and I laughed and continued the march toward the assigned position.

Monday April 26

Calm morning. Starting at midday, the Germans throw over some big bombs. We respond with trench artillery. The 75s, through some undoubtedly well placed vollies of shells, silence them.

Tuesday April 27

Until 10:00 am, a calm too lovely reigned from one part of the front to another, which foreshadows nothing good. One senses an approaching "storm." Indeed, around 10:15, the Germans begin to rain down, non-stop, big bombs on the sector. What a nuisance! It's just at the moment when the cooks have chosen to bring up the boilers and canteens for the big morning meal...We are forced to leave our mess-kits. There's no laughing now, for this time it's heavy calibers which are falling on us non-stop. We're in a state of high-alert. We have a head ache from following the path and trajectory of the Minemm [sic]. An infernal racket is produced by the unending explosions, which is amplified even louder in the ravine. From our side, the 75s go into action. It a huge uproar which lasts until 3:00 pm.

A moment of calm and, immediately following an order is passed down to the first lines in front of us to evacuate the trenches in order to allow our artillery (light and heavy) to fire without hurting our men, even though the 75 is highly accurate and effective. Our section stays on high-alert in a communication trench covered with logs. We don't know what's happening, but we witness a hellish dance. We can no longer hear ourselves speaking. Ten, twenty, thirty shells explode on the German lines simultaneously. We listen to an uninterrupted whistling followed by terrific explosions. Those who have not lived through these moments can't really know what it feels like.

This bombardment lasts for about an hour. We go to take our places and take a careful count, after this demonstration, we rest a bit during the night. I rolled myself up in a blanket at the bottom of the trench along with my comrades, and broken with fatigue, our eyes close without delay. Don't think that we have any sort of bed. Here, we lie out on the ground, with a stone or the pack serving as a pillow. I assure you that sleep came quickly. Hardly an hour had passed (it was 8:00 pm) since we had fallen into the land of sleep, when we were awoken with a jolt by an intense fusillade. We immediately grab our rifles, checking our cartridge supply. A few minutes later, it was the big dance: grenades, shells, bombs, etc. The Germans were attacking us. We wait in our second line trench for the order to move forward. We've fixed bayonets. At 9:00 pm, calm settles back. We hadn't been needed, the German attack had failed and we learned that they had been repulsed with heavy losses. On our side, in our reserves trenches, we had two killed and a dozen wounded. We stayed in a state of alert until the next morning. In other words, with the weapon ready and sleep pushed off till later. Nothing out of the ordinary occurs for the rest of the night.

Wednesday April 28

At 8:00 am, the enemy bombs start up once again. We're still in reserve in the second line. Bursts go off basically everywhere, but soon the fire slackens and calm resumes. It remains like this until 9:30 pm. At this moment, we are relieved by the 328th Infantry. We go to rest at La Harazée. Our first journey to the trenches is over, without, thank heavens, too many losses. Despite this, about twenty poilus from our company have fallen, to never rise again.

[Friday] April 29

I start to feel the fatigue owing to basically six days without sleep. But with a bit of rest and the life in the open air, we haven't lost our appetite. The same evening, we are finally ready to renew our exploits...

Saturday May 1

This time, at 5:30 am, the assembly and departure for Croix-Gentin, a camp located in the Gruerie Wood. We arrive a bit tired from our long march. We have a good night of rest. At daybreak, we hear the cannonade from the Vienne-le-Château side, the sector occupied by the 40th Division (we've left the 42nd, which marches together with the 40th). It's heating up over there.

Sunday May 2

The morning sun warms us up. Its rays light up this mysterious forest as we breathe in its pure air. It's a renewal. Spring, even in war-time, has its good side. I gather some small flowers to put in the letter to my mother. At 9:00 am, with new comrades, I help with the open-air mass, said by the chaplain. The improvised altar is made from empty crates decorated with green leaves and flowers. It's the start of a "good rest." We experience an inner joy as we listen to the good words of the soldier-priest. To us, he is more than a great friend: he is a father who we love. My comrades Hannois, Guillou and Genevoix are at my side. The service over, we go back joyfully to our billets. A nice stroll in the forest has made us all better. The following day, the same schedule.