The System of National Conscription of France, 1873-1914

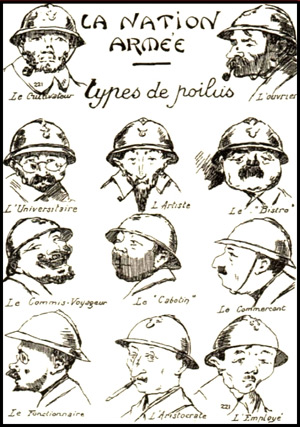

Illustration from the trench paper, "L'Echo des Marmites."

Universal conscription began in France in 1793. Since 1905, all fit Frenchmen (or naturalized Frenchmen) were required to serve in the military for a total of 25 years, beginning the year in which they turned 21 years of age. This 25 years encompassed the periods he served in the active, reserve and territorial armies respectively. This commitment would later be increased to 28 years in 1913 and the recruitment age dropped to 20.

Law of July 1873 -- Creation of the Army-Corps Regions

The basic organization of the French army under the Third Republic was shaped by the Law of July 24, 1873. Under this law, the territory of "metropolitan" (i.e. continental) France was divided into eighteen army-corps regions, these being established in accordance with the then existing resources of recruiting and the necessities of mobilization. Each was self-contained in arms, ammunition, supply, transport, clothing and equipment for the entire troop force therein. Generally, each region contained roughly 200,000 at the date of the laws passing. However, the actual number of men called up from year to year depended on the need as determined by the War Ministry. This was decided by lottery. The year following this (1874), Algeria would be made a separate army-corps region, bringing the total up to nineteen. Due to their size and massive populations, in 1875 the cities of Paris and Lyon would form their own military governments that were superior to the civilian states. To adapt to the changing strategic situation as regards to the frontier bordering Germany, a redivision of this large zone was necessary. Subsequently, on December 5, 1897 the 20th army-corps region was constituted. Finally, on December 22, 1913, the 21st army-corps was created. Thus, at the outbreak of war, the army-corps regions were the following:

1st (Lille)

2nd (Amiens)

3rd (Rouen)

4th (Le Mans)

5th (Orléans)

6th (Châlons-sur-Marne)

7th (Besançon)

8th (Bourges)

9th (Tours)

10th (Rennes)

11th (Nantes)

12th (Limoges)

13th (Clermont-Ferrand)

14th (Lyon)

15th (Marseille)

16th (Montpellier)

17th (Toulouse)

18th (Bordeaux)

19th (Algeria)

20th (Nancy)

21st (Epinal)

Military Government of Paris

Military Government of Lyon

Click for a Map of the Army Corps Regions

For a color map, see this siteOf the twenty-one army-corps comprising the French metropolitan army, all were stationed in France except for the 19th Corps which was constituted differently than the rest and was quartered in Algeria. A separate "Occupation Division" was stationed in Tunisia.

Region Subdivisions and Recruiting Offices

Each army corps region was divided into a varying number of subdivisions de région ("region subdivisions"). Normally there were eight subdivisions in a region. Exceptions to this rule were the 6th Corps with four subdivisions, the 7th with six, the 15th with nine, the 20th with four and the 21st with two. It is also necessary to note that the regional organization did not exist in North Africa. In principle, a bureau de recrutement et mobilisaton ("recruitment and mobilization office") was located in each subdivision (normally the largest town of the area). Besides the 159 subdivision recruiting offices, there were 14 additional offices: three at Lyons, one at Versailles, six in the Seine department, three in Algeria, one in Gaudeloupe, one in Réunion, one in Martinique, and one in Tunisia. The recruiting offices handled the incorporation of the annual class of recruits and the recall of reserves for training or mobilization. In addition, it was responsible for requisitioning, including that of horses, mules and wagons. In case of mobilization, all troops were to be recruited to war strength from the resources of the region. A recruit's subdivision town was normally determined by proximity -- he would report to whichever subdivision town was closest to his home.

After various modifications, a final law passed on December 22, 1913 marked the final territorial reorganization of France before the war, with the military regions remaining fixed until October 1919. This is shown in the table below, with the largest subdivision (from which the army corps region acquired its name) indicated in bold (Note: worth remembering is that prior to 1914, conscripts who completed their service prior to 1914 would have not necessarily been processed under this exact regional system).

The Military Regions and Subdivisions of France, December 1913

| Lille, Valenciennes, Cambrai, Avesnes, Arras, Béthune, Saint-Omer, Dunkerque | Nord and Pas-de-Calais | |

| Amiens, Mézière, Saint-Quentin, Beauvais, Abbeville, Laon, Péronne | Aisne (discluding the districts of Soissons and Château-Thierry), Oise (excluding the districts of Compiègne and Senlis), Somme, the district of Pontoise (in Seine-et-Oise depart.), the districts of Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen, Aubervilliers, Noisy-le-Sec and Pantin (in the Seine depart.), the 10th, 19th and 20th Arrndts of Paris, Ardennes (districts of Rocroy, Sedan and Mézières), Meuse district of Montmédy), Meurthe-et-Moselle (districts of Longuyon, Longuy and Audun) | |

| Rouen, Rouen Nord, Rouen Sud, Le Havre, Caen, Evreux, Falaise, Lisieux, Bernay | Calvados, Eure, Seine inférieure, the districts of Mantes and Versailles (in the Seine-et-Oise dept.), the districts of Courbevoie, Puteaux, Asnières, Boulogne-Billancourt, Levallois-Perret, Clichy, Colombes and Neuilly (in the Seine dept.) and the 1st, 7th, 15th and 16th Arrndts of Paris | |

| Le Mans, Mayenne, Dreux, Mamers, Chartres, Alençon, Argentan, Laval | Mayenne, Sarthe, Eure-et-Loire, Orne, the district of Rambouillet (in the Seine-et-Oise dept.), the districts of Ivry, Vanves, Villejuif and Sceaux (in the Seine dept.) and the 4th, 5th, 6th, 13th and 14th Arrndts of Paris | |

| Orléans, Fontainebleau, Melun, Coulommiers, Auxerre, Montargis, Blois, Sens | Loiret, Loire-et-Cher, Seine-et-Marne, Yonne, the districts of Corbeil and Etampes (in the Seine-et-Oise dept.), the districts of Charenton, Nogent-sur-Marne, Saint-Maur, Montreuil, and Vincennes (in the Seine dept.) and the 2nd, 3rd, 11th and 12th Arrndts of Paris | |

| Châlons-sur-Marne, Reims, Verdun, Compiègne, Soissons | Aisne (districts of Soissons and Château-Thierry), Oise (districts of Compiègne and Senlis), Ardennes (districts of Vouziers and Rethel), Marne, Meuse (districts of Verdun, Bar-le-Duc and Commercy), a part of Meurthe-et-Moselle department (districts of Briey, Conflans, Chambley, Pont-à-Mousson, Triaucourt), and the 8th, 9th, 17th, 18th Arrdts of Paris. | |

| Besançon, Belfort, Vesoul, Lons-Le-Saunier, Bourg, Belley, Mulhouse | Ain, Doubs, territory of Belfort, Haute-Saône (excluding the district of Gray), Vosges district of Saint-Dié, district of Gérardmer, the district of Remiremont and districts of Redon-l'Erape, Rambervillers and Rhône (4th and 5th districts of Lyon, the district of Villefranche, the districts of l'Arbresle, Condrieu, Limonest, Mornant, Neuville, Saint-Symphorien and Vaugneray) | |

| Bourges, Auxonne, Dijon, Chalon-sur-Saône, Mâcon, Cosne, Autun, Nevers | Cher, Côte-d'Or, Nièvre, Saône-et-Loire | |

| Tours, Châteauroux, Le Blanc, Parthenay, Poitiers, Chatellerault, Angers, Cholet | Maine-et-Loire, Indre-et-Loire, Indre, Deux-Sèvres and Vienne | |

| Rennes, Guingamp, Saint-Brieuc, Vitre, Cherbourg, Saint-Malo, Granville, Saint-Lô | Côtes du Nord, Manche et Ille-et-Vilaine | |

| Nantes, Ancenis, La-Roche-sur-Yon, Fontenay-Le-Comte, Vannes, Quimper, Brest, Lorient | Finistère, Loire inférieure, Morbihan and Vendée | |

| Limoges, Magnac, Laval, Guéret, Tulle, Périgueux, Angoulême, Brive, Bergerac | Charente, Corrèze, Creuse, Dordogne, Haute-Vienne | |

| Clermont-Ferrand, Riom, Montluçon, Aurillac, Le Puy, Saint-Etienne, Montbrisson, Roanne | Allier, Loire, Puy-de-Dôme, Haute-Loire and Cantal | |

| Grenoble, Bourgouin, Annecy, Chambéry, Vienne, Romans, Montélimar, Gap | Hautes-Alpes, Drôme, Isère, Savoie, Haute-Savoie, Basses-Alpes (districts of Saint-Paul, Barcelonnette and Lauzet), Rhône (districts of Givors, Saint-Genis, Laval, Villerbanne, 1st, 2nd, 3rd et 6th districts of Lyon | |

| Marseille, Digne, Nice, Toulon, Nîmes, Avignon, Privas, Pont-Saint-Esprit, Ajaccio | Basses-Alpes discluding the districts of Saint-Paul, Barcelonnette and Lauzet), Alpes-maritimes, Ardèche, Bouches-du-Rhône, Corse, Gard, Var and Vaucluse | |

| Montpellier, Béziers, Mende, Rodez, Narbonne, Perpignan, Carcassonne, Albi | Aude, Aveyron, Hérault, Lozère, Tarn, Pyrénées-orientales | |

| Toulouse, Agen, Marmande, Cahors, Montauban, Foix, Mirande, Saint-Gaudens | Ariège, Haute-Garonne, Gers, Lot, Lot-et-Garonne, Tarn-et-Garonne | |

| Saintes, La Rochelle, Libourne, Bordeaux, Mont-de-Marsan, Bayonne, Pau, Tarbes | Charente-inférieure, Gironde, Landes, Basses-Pyrénées and Hautes-Pyrénées | |

| Alger, Oran, Constantine | Alger, Oran, Constantine | |

| Nancy, Toul, Neufchâteau, Troyes | Haute-Marne (districts of Wassy and Chaumont, discluding the districts of Chaumont, Arc-en-Barrois, Châteauvillain and Nogent-en-Bassigny), Vosges (districts of Neufchâteau and districts of Charmes, Mirecourt and Vittel), Aube, Meurthe-et-Moselle (discluding the districts of Briey and the districts of Pont-à-Mousson, Thiaucourt, Blâmont, Cirey, Badonviller, Baccarat) | |

| Epinal, Langres | Haute-Saône (district of Gray), Haute-Marne (district of Langres, districts of Arc-en-Barrois, Châteauvillain, Chaumont, Nogent-en-Bassigny), Vosges (districts of Epinal, Miraucourt (the districts of Darney, Dompaire, Monthureux-sur-Saône), Meurthe-et-Moselle (districts of Blamont, Cirey, Badonviller, Baccarat) | |

of Paris |

Seine (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th offices) Seine-et-Oise (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th Corps) |

1st office: (Barracks-Post No. 5) Porte de la Chapelle-Saint-Denis for the 10th, 19th, 20th Arrdts of Paris, St-Denis, St-Ouen, Aubervilliers, Pantin, Noisy-le-Sec. Designated for the II Corps. 2nd office: (Barracks-Post No. 8) Porte de Passy for the 1st, 7th, 15th, 16th Arrdts of Paris, Courbevoie, Puteaux, Asnières, Neuilly, Boulogne-Billancourt, Levallois-Perret, Clichy, Colombes. Designated for the III Corps. 3rd office: (Barracks-Post No. 12) Porte de Chatillon for the 4th, 5th, 6th, 13th, 14th Arrdts of Paris, Sceaux, Vanves, Villejuif, Ivry. Designated for the IV Corps. 4th office: (Barracks-Post No. 1) Porte de Charenton for the 2nd, 3rd, 11th, 12th Arrdts of Paris, Charenton, Nogent-sur-Marne, St-Maur, Vincennes, Montreuil. Designated for the V Corps. 5th office: (Barracks-Post No. 6) Central Admin. Office of the Seine (71 Saint-Dominique Street, Paris) 6th office: (Barracks-Post No. 7) Porte de Champerret for the 8th, 9th, 17th, 18th Arrdts of Paris. Designated for the VI Corps. |

of Lyon |

Rhône (Lyon Central, Lyon Nord, Lyon Sud) |

*See additional allotments of subdivisions to these army corps regions below.

Covering Corps

To face the looming threat of a united Germany, a Corps de Coverture ("Covering Corps"), a sort of screening force, was created to provide a readily-available force in the event of invasion. This force was constituted from the 4th Battalion of each regiment based in the army corps regions that faced the eastern frontier, along the Belgium-German (Alsace-Lorraine)-Swiss border. From north to south, these were the 2nd, 6th, 20th, 21st and 7th army corps. While all other metropolitan regiments had their 4th Battalions phased out from 1902-1907, the regiments in these regions were required to maintain a higher number of men under arms in peace time than those of the "interior" regions. For example, the size of an infantry company in an interior region in peace-time was 140 men while that of a "covering" region was 200. Likewise with a company field artillery (120 men compared to 160) and engineers (120 compared to 160).

These 4th Battalions were initially detached from their regiments and assigned to the fortified zones, where they substituted for the regional regiments and were integrated into the new divisions making up part of the army corps. On March 19, 1913, these battalions are regrouped into 10 regiments (numbered 164-173) which were detached from the army corps. Upon mobilization, the active corps were composed of three battalions (of 4 companies each), thanks to the call up of reservists, and the effectives of the regiment went from 1,800 or 2,500 to 3,400 men. Additionally, in each region subdivision of the border regions (6th, 7th, 20th and 21st Army Corps and the 4th division of the 2nd Corps), a territorial regiment was mobilized as a covering force.

However, the frontier regions (which included Verdun, from where the 151st RI was stationed) could not supply enough men to fill the ranks of the units of their corresponding army corps. Consequently, crowded urban centers such as Paris and Lyon supplied additional recruits to the Corps de Couverture. The 6th Corps was specifically allotted a certain district in Paris. Additionally, a certain number of reservists living near the fortified zones of Belfort, Epinal, Verdun or Toul could be called up by local garrisons upon mobilization to give them an immediate boost in effectives.

Displacement of Subdivisions and Recruiting Offices

With the invasion and occupation of the German army in the summer and fall of 1914, the system of military regions in France had to be reorganized. Seven army corps regions had to partially or wholly relocate their recruitment offices: the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th, 7th, 20th, 21st regions, the 6th Seine office, the Central Office and the Seine-et-Oise office. Thus, the recruitment offices of the 1st region transferred into the 12th, those of the 2nd into the 11th, those of 6th into the 4th, those of the 7th into the 13th, those of the 20th into the 5th, and the office of the 21st into the 18th. The Central Office is evacuated to Bordeaux with the French government Gouvernement, along with that of the Seine-et-Oise. The Seine 6th office is transferred to Pauillac. The new locations of the recruiting offices as of September 8, 1914 are as follows:

Relocations of the Recruiting Offices of Occupied Regions, Sept. 1914

Corps Regions |

||

|---|---|---|

| Lille Valenciennes Cambrai Avesnes Arras Béthune Saint-Omer Dunkerque |

Limoges Guéret Tulle Brive Cognac Périgueux Bergerac Sarlat |

|

| Mézières Saint-Quentin Beauvais Amiens Abbeville Laon Péronne |

Nantes Quimper Brest Morlaix Landerneau Lorient Ancenis |

|

| Fontainebleau Melun Coulommiers |

Mende Albi Rodez |

|

| Verdun Reims Soissons Compiègne Châlons-sur-Marne |

Rennes Chartres Le Mans Le Mans Rennes |

|

| Belfort Vesoul |

Clermont-Ferrand Clermont-Ferrand |

|

| Toul Nancy |

Troyes Troyes |

|

| Epinal |

Chaumont |

|

| Central Office 6th Seine Office Seine-et-Oise Office |

Bordeaux Pauillac Bordeaux |

Thirty-six out of 155 recruitment offices in France are displaced to the safe zones and are set up by the end of September 1914. Though they no longer occupy the same geographic sector, they continue to receive the same allotted recruits as in peace time. The displaced recruitment offices are placed under the orders of the territorial authorities of the region to which they were evacuated. Therefore, the offices of Beauvais, Amiens, Abbeville, Béthune, Boulogne, Arras and Lille were placed under the orders of the general commanding the region of the Nord. The offices of Valenciennes, Cambrai, Avesnes, Mézières, Saint-Quentin, Péronne, Laon and Dunkerque were subordinate to the authority of the region generals of the 11th and 12th. With the stabilization of the front line and the beginning of trench warfare, many of these offices returned to their original location. From October 1914, in the 2nd region, the Beauvais office set up in its original locality. It ws the same for those offices of the 5th region, those from Reims, Compiègne and Châlons-sur-Marne in the 6th, Vesoul in the 7th, Toul in the 20th, and all the offices of the Seine and Seine-et-Oise.

Progressively up through the summer of 1915, a great number of offices will be able to return to their original locations. In November 1914, the offices of Vesoul and Neufchâteau were back in their respective subdivisions. In January 1915, the trend continued, as the offices of the 20th and 21st regions were reintroduced into their subdivisions. Only the Reims offices in the 6th region had to be displaced once more to Châlons-sur-Marne, while those of Soissons (transferred to Oulchy-le-Château) and Verdun (transferred to Bar-le-Duc) are brought closer to their original subdivision. In July 1915, the list of offices displaced is definitively set with the exception of those from the 7th region returning later on. The French High-Command would no longer transfer any offices, aside from two which were brought closer to their original subdivision (the Arras office set up at Boulogne-sur-Mer in November 1915 and the Lille office to the same town in December 1915. As it stood on November 11, 1914 though, the displaced recruitment offices consisted of the following:

Relocations of the Recruiting Offices of Occupied Regions, Nov. 1914

Corps Regions |

||

|---|---|---|

| Lille Valenciennes Cambrai Avesnes Arras Béthune Saint-Omer Dunkerque |

Limoges Guéret Tulle Brive Cognac Périgueux Bergerac Sarlat |

|

| Mézières Saint-Quentin Amiens Abbeville Laon Péronne |

Nantes Quimper Morlaix Landerneau Lorient Ancenis |

|

| Verdun Soissons |

Rennes Chartres |

|

| Belfort |

Clermont-Ferrand |

|

| Nancy |

Troyes |

|

| Epinal |

Chaumont |

Recruiting

French army’s system of recruitment was based on regional conscription. Each regiment was assigned a home garrison and drew their men from the municipal districts in the vicinity of that garrison. This meant that, in general, recruits were assigned to a unit in the same army corps region in which they lived and often to one based in their subdivision or the next closest subdivision possible. In principle, however, men were never posted to a unit stationed in their hometown. In such cases when a unit was stationed in a man's hometown, he was sent to the next closest unit. As much as possible, the men of each subdivision were kept together and were always sent to the same army corps. A man would thus have an idea of which region he was likely to serve in. However, under the existing system, each army corps region was allotted a certain number of men. Thus, the excess number of men of one subdivision/army corps region would be sent to another subdivisions/army corps regions which was in deficit.

For the reservists, there were more exceptions to the normal practice of being assigned to a local unit. One such case was when a man lived near a frontier garrison. Because the Corps de Couverture required a certain portion of reservists readily at hand, a circle was drawn around each frontier garrison which incorporated a certain number of rural districts. These districts had to then supply a portion of their reservists to the Corps de Couverture. These men were capable of being mobilized within a few hours time.

Though as new recruits men did not necessarily fulfill their active three-year service with the unit closest to their homes, when they became reservists they were normally allotted to regiments as near to their homes as possible (though there were exceptions to this as well). Furthermore, men who were married or supported a family could apply for a "special assignment" in order to serve in the garrison nearest their home. The territorial army operated under the same basic principles as the reserve army, with an added focus on keeping men as nearest their home as possible.

As noted above, the frontier regions could not supply enough men to fill the ranks of the units of their corresponding army corps. The shortfall was compensated by the allotment of additional recruits from crowded urban centers throughout France to the Corps de Couverture. Generally speaking though, with only few exceptions, mobilization would only entail short journeys on the part of reservists.

Mobilization

The subdivision headquarters was responsible for coordinating the mobilization of men in their assigned area. Notification of mobilization came either by a letter addressed to his home or via posters and pamphlets being displayed in public areas. A man was to report to his depot by a date specified in the notice of mobilization. Free transportation was provided by rail to the destination for all men reporting for duty. Once at the depot, the man would be outfitted with his uniforms, equipment and arms.

Two Years Law of 1905 -- Class System

A soldier's service was defined by two distinctive classes: the classe de recrutement and the classe de mobilisation. Until 1905, not every man of the qualifying age was called up: selection was by ballot of those eligible to serve, and there were many exemptions. The number of exemptions were reduced in 1889, along with a reduction to three years of active service. With the passage of the Two Years Law of 1905, active service requirements were reduced again to simply two years, and nearly all exemptions were abolished with service being virtually obligatory.

Starting in 1905, a man's classe de recrutement ("recruitment class") was the year in which he turned 20 (and was thus determined by his birth year) or the year in which he was drafted. A man born in 1891 would thus belong to the class of 1911. A soldier was always referred to by his recruitment class -- this was his "class year." The classe de mobilisation ("mobilization class") was the year in which the man was actually incorporated into military service, normally the year following his recruitment class year (at the age of 21). However, for those incapable of service for a given reason, or for those who had enlisted voluntarily before or after (in those cases where a deferment had been awarded) their recruitment class, their mobilization class was determined by the year in which they entered into the service. Therefore, a man born in 1880, who belongs to the class of 1900, but who has enlisted voluntarily in 1898, belongs to the mobilization class of 1898.

The specific date of mobilization for each class was October 1 (of their mobilization class year). For example, the class of 1910 began their military service on October 1, 1911 (the year in which the men turned 21 years of age). The "Two Years Law" saw a reduction of soldier's active army service obligation to 2 years. From 1875 until the passage of this law, a soldier's total commitment of service had been 25 years, including 3 in the active army, 7 in the reserve, 6 in the territorial and 9 in the territorial reserve. In 1892, this was altered to 3, 10, 6 and 6, respectively. The "Two Years Law" altered this allotment to 2 years active, 11 years reserve, and 6 years for the territorial and territorial reserve each. To make the situation more egalitarian, the privilege of shortening a man's period of service owed if he were a student or had earned a diploma was suppressed. Those admitted through to the special military schools after passing the competitive entrance exams were now obliged to serve a year in a troop formation before definitively becoming graduates of Saint-Cyr or the Ecole Polytechnique. After spending a year in a regiment learning practical skills and the life of the soldier (to whom they will later command), the candidates will enter the military school for two years as a student-officer.

Every January, a list of men eligible for service by age was posted in each commune. Those listed were obliged to appear before a board consisting of a general officer, the departmental prefect and other representatives of local government. Every man was measured and weighed by a medical officer. Some men had their call-up immediately postponed because of lack of stature, while others were excluded on grounds of congenial infirmity. Convicted felons were no exceptions to the draft and were called up just the same. Those who were in prison when their call-up arrived were permitted to serve out their sentence in the brutal Battalions d'Infanterie Légère d'Afrique (B.I.L.A.) -- African Light Infantry Battalions. In 1914, these were formed into battalions de marche though these remained garrisoned in North Africa at first. Later, three B.M.I.L.A.s were sent to France: the 1st, 2nd and 3rd B.M.I.L.A.s., with the 3rd and later 5th being formed in France.

Three Years Law of 1913 -- Extended Service and the Mobilization of Classes

The Three Years Law of May 1913 made for changes in the class system. This was done mostly in anticipation of the approaching conflict and with a desire to rapidly increase the size of their active army. Henceforward, a class would be incorporated into military service in October of the same year of its recruitment (i.e. its recruitment class year). Thus, recruits of the class of 1913 were inducted at the age of 20 instead of 21. For all intents and purposes, the recruitment class year and the mobilization class year for conscripts had become one in the same, with the year by which the class was known and its year of actual incorporation being synced together. As a result of the law, two classes were called up in 1913: the class of 1912 in October 1913 (the last class to be incorporated under the old rules) and the class of 1913 in November 1913. The one-month gap between incorporation dates of these two classes was allotted in order to ease the strain caused by a doubling in the number of recruits being called up in one year. The class of 1911 had its length of active service extended by a year, to October 1914. The class of 1914 would be the first class called up as regulated under the new system, on October 1, 1914.

Additionally, each soldier now had to serve a total of 28 years, including three in the active army (hence, "Three Years Law"). The lengthened term of service that was brought about by the Three-Years Law was retrograded. Thus, the 1887 and younger classes would be required to serve 28 years as well. This broke down into the following terms:

Active army..............................3 years

Active reserve army.................11 years

Territorial army........................7 years

Territorial reserve army...........7 years

Total service............................28 years

The short term effect of the Three-Years Law saw a boost in the number of active duty servicemen, with two new classes being called up simultaneously and those classes already in active service (the classes of 1911 and 1910) having their service extended a year. The average class size for the years of 1906-13 was 223,000. The average class size for the years of 1914-18 was 280,000 men.

In general, the younger classes of (active) reserves (e.g. the classes of 1907-10) were assigned to active units in order to bring them up to war strength. The older classes (e.g. the classes of 1903-06) formed their separate reserve units, which were both employed alongside active units in the field or acted as support forces. However, many highly qualified and professional reserve soldiers and officers were called on to serve in the active army when war broke out. The demarcation between active and reserve units was erased almost as soon as hostilities began. Territorial units were originally intended to be used as interior garrison troops and work battalions. While territorials continued to serve in this function throughout the war, some units would serve in combat roles in times of need. Additionally, those men serving in the territorials who were considered to be fit physically fit enough were eligible to be transferred to active or reserve units for front line service, a practice which began in 1915.

A study of class years reveals the wide spectrum of age represented in the French army during the war. In August 1914, the classes first called to the colors encompassed the following cohorts and age groups:

Active classes: 1911-1913...............ages 20-23

Reserve classes: 1900-1910............ages 24-34

Territorial classes: 1896-1899..........ages 35-38

In the face of unsustainable losses in the first months of the war, the "war-time" classes were called up progressively earlier and earlier, and the oldest territorial classes were called back. The following is a complete table of class year and mustering schedule:

Physical Fitness Standards

A declining birthrate in France had made it necessary for military authorities to forego any idea of selection in recruitment in the years leading up to the war, regardless of height (the average height of a French soldier was 5' 6") or weight (unless the man was obviously unfit). Only the cavalry and artillery still maintained some standards. However, there was a loose system established which fed men into certain categories of service. They broke down into the following: 1) men fit for ordinary service; 2) men fit for auxiliary service (i.e. clerking); 3) men of "weak constitution" who were recycled for reexamination the following year; and 4) men unfit for any service and were totally exempt from military service.

To illustrate the acceptance rate of new recruits, for the class of 1914, of 318,464 elligible to be called up, 292,447 are incorporated into the army, or roughly 92%. For the class of 1917, 313,070 men were elligible of which 297,402 were incorporated -- nearly 95% acceptance rate. Of these, the vast majority (normally 90%) went to the infantry. Service in the engineers and artillery was normally reserved for those who has worked on the railroads or in public works, shipyards and telecommunications. However, by 1917 and 1918, more and more men were siphoned off to the artillery where this standard no longer applied.

Pay

For pay, a private in the French army made 1 sou (5 centimes) per day. A sou was equivalent to about 1 cent. For reference, 30 sous (one month's pay) was equal to 1.50 francs. Thus, the French soldier was paid literally in pennies. In August 1914, an additional allowance of 1.25 francs was given to soldier's who had to support a family, with another 50 centimes for each child under sixteen years of age for those families in need. Later, the government would supplement this daily pay with a trench allowance (i.e. combat pay) of 1 franc per day when at the front, although half of this was held back as a sort of post-service pension. This irked the soldiers to no end, since many knew they would not survive the war to spend it. Following the mutinies in the spring and summer of 1917, the trench allowance was raised to 2 Francs per day. Additionally, there was a welfare allowance of 10 sous for each child under the age of 16, for those soldiers who were in need of government assistance.

War-time Changes to the System of Conscription

Naturally, the benefit of recruiting locally (creating a stronger bond between soldiers who were from the same locality) would also prove a liability. When a particular regiment, brigade or even division composed of men all from the same area took a beating in battle, the loss in life and limb was concentrated geographically as well. Thus, a series of neighboring towns could wake up one day to find all of its young men dead or injured. The pre-war recruitment practice continued to be maintained into the first months of the Great War, buoyed by the new recruits of incoming class of 1914, who were mustered into service in September 1914. Yet the reliance of drawing replacements for depleted units based on the conscript's home region could ultimately not be maintained in the face of such heavy and sustained losses as experienced in the battles of the Great War.

In a shift away from the pre-war system, starting in the winter of 1914-15 a process known as brassage ("mixing") was introduced. No longer would men from the same subdivision region be sent to the same unit. Instead, they would be dispersed into units belonging to different military regions depending on where the manpower need was greatest. Ad hoc, this began to occur at the end of 1914 when new recruits and recuperated soldiers (who had been wounded in service and were able to return to active duty) started being transferred to different units other than their home garrison formation. The brassage was further accelerated by a change in how reinforcements were constituted and then allotted to units.

For the first year of the war, recruits first reported to their home depots for basic training and upon completion, were then sent to their assigned units. Beginning in August 1915, in an effort to improve the training, on August 14, 1915 a ministerial decision called for the creation of 18 Battalions de Dépôt ("Depot Battalions"), each being numbered as the 9th Battalion of such and such regiment. These were also referred to as battalions d’instruction ("instruction battalions"). Theoretically, there was to be at least one 9e Bataillon per military region. In other words, there was not a one-for-one ratio of regiment to depot battalion. In practice, some regiments were ordered to provide effectives for these battalions while others were exempt. In addition, the regiments at the front did not necessarily received reinforcements from their own military region. The battalions were constituted using drafts from the various regiments of each military region, the number of effectives being sourced from each regiment typically varying from one company to two companies. The battalions d’instruction (B.I.) were attached to Centres d’Instruction d'Armée ("Army Instruction Centers"), located in the Armies Zone just behind the front lines. Until 1916 these were also known as Depot Divisionnaires (“Divisional Depots”) and then later as Centres d’Instruction Divisionnaires (“Divisional Instruction Centers”).

Upon being called up, new recruits would report to duty at the regimental depot (constituted by the “missing” companies of the regiment and numbered 13 to 16) for basic training. Following the training received at the regimental depots, coupled with the completion of field exercises with the 7th Battalion of the regiment (companies numbered 25 to 28), the recruits were then transferred to the Centres d’Instruction d'Armée (C.I.A.). Having received the available contingent of men formed in the regimental depots, C.I.A. then distributed the contingents between the various B.I.s that they administered. It was here where the first level of "mixing" took place, as the recruits were transferred to a 9th Battalion of a regiment from their Military Region but not necessarily to the battalion of their home regiment. (Moreover, the 9th Battalions were not necessarily composed of men from the originating regiment).

After completing their advanced training with the B.I.s, the recruits were then assigned and transferred to the units in the line as determined by which ever unit was in need of reinforcements. Hence, the men were not necessarily sent to the regiments from their local subdivision, but could be sent to any regiment belonging to the army administering the C.I.A. And so at this stage another round of mixing would take place. After completing their training, the recruits would then be assigned and transferred to the units in the line as determined by which ever unit was in need of reinforcements. Similarly, recuperated soldiers were processed first through the depots of their previous unit before being assigned to a unit at the front. Commonly, new recruits were sent up to the line together with a contingent of recuperated vets. Once the men arrived at the unit, they would then be divvied up between the companies on an as-needed basis. Once the men arrived at the unit, they would then be divvied up between the companies on an as-needed basis. It was in this way that Normans were mixed with Creusois, Bretons with Varois, Parisiens with Bordeaux, etc., etc.1

An unintended negative consequence of this brassage soon became evident. Feelings of isolation and alienation ensued amongst men often far away from home and surrounded by strangers who they might have difficulty relating to. Aside from this there was the more pressing issue that men in the same unit could not understand each other. France at this time in its history was highly regionalized, with certain areas not only having different customs and traditions but even different patois (dialects). There was Alsatian, Basque, Breton, Catalan, Coursican, Franconian, Gasçon, Languedoc, Maghreb Arabic and Walloon, just to name a few. Subsequently, there were examples of men in the same company not being able to comprehend one another and officers being unable to properly command their men due to language barriers. In part, this is why the soldiers would develop their own unique military patois that they could all understand (see the French Military Terms and Soldier Slang page for more information). Despite the difficulties however, the adoption of proper French as the national language was accelerated as well.

The question of how long a regiment or battalion managed to retain it's original, unique regional character varies greatly from unit to unit. Those units that saw less combat naturally had less turn-over in the ranks. Reserve units, territorials, and other rear-echelon units generally speaking suffered fewer losses than active units serving in the front lines throughout the four and half years of war. Even for those less engaged, by 1917 and 1918 enough of the original corps had been killed or wounded and replaced by new men that brassage had run its course. For the average line infantry regiment, consistent heavy losses in battle after battle, could mean a loss of their regional identity beginning as early as 1915.