Transportation of Rations

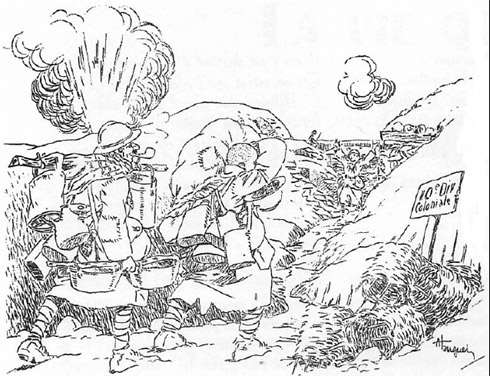

'Mess-Men,' A. Buguel, 'Le Petit Écho du 18e'

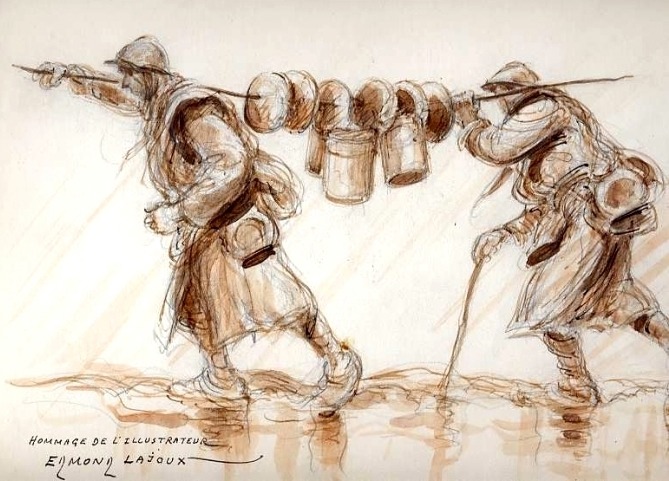

Upon arriving at the field kitchens, the cooks would distribute out the food and drink, transferring the food to the various containers. Cooked food, usually a soup, casserole or rice, was placed in the Bouthéon stew-pots, the name universally mutated by logical assimilation to bouteillon ('bottle') due to the closeness in pronunciation. The large camp mess-pan called the plat-á-quatre ("plate for four") could also be used to carry up food that wouldn’t spill. The loaves of bread were carried either by stringing the loaves together with twine to make a bandolier or by impaling the loaves onto a stake which was then supported on the shoulders. Canned foods were carried either in haversacks or the large canvas distribution sacks. Though the food was hot when it was in the rear, by the time it arrived at the front it had already turned cold. The beverages --pinard (“wine”), coffee and water were brought up in the individual canteens as well as in the bouteillons or squad canvas buckets.

With the receptacles filled with food and drinks, the heavily burdened hommes-soupe would then make the long, tedious journey back to their company. Bedecked with stew-pots, mess-pans, canvas buckets, sacks, loaves of bread and dozens of filled canteens, there was a degree of ludicrousness to the scene. Paradoxically, the hommes-soupe took on the role of both savior and vexor to their hungry comrades waiting for their meal. Despite their best efforts, the food and coffee often became luke-warm or cold by the time it reached the front lines. This always drew complaints from the men in their damp, muddy trenches who, as a result, often went a week or more without a single hot meal. Simon Hastoy was able to sympathize somewhat with the soup-men: “At ten o’clock the cooks arrive . . . they’re carrying the soup, a bit of meat and bread. You can guess what the stew’s like – always cold, because the poor fellows have had to carry it for three or four kilometers.”